Non-Reductive Materialism: Can Physicalists Have Their Cake and Choose to Have It Too?

Consciousness Theories. Physicalism #7

Welcome to Part 7 and the last article in our series on physicalism (the theory that the physical world can fully explain consciousness).

If you're new here, hello and welcome! I’m glad you’re here. This article is part of a series, and it will draw heavily on concepts covered in earlier articles. If you are new to the philosophy of mind, you may find the earlier articles helpful for understanding this one.

Functionalism: Why the Most Popular Consciousness Theory Might be Wrong

Does the Mind Exist? Understanding Eliminative Materialism

We've explored a lot in this series, but at the centre of all of it is one key question:

How do our thoughts, feelings, beliefs and choices fit in a world made of physical stuff?

Our thoughts and decisions don't feel like they're just the result of neurons firing in our brains. Mental events, we assume, are surely more than just a complex series of physical events.

And yet, if we want a physicalist theory, we are going to have to ground those mental events in the physical world.

In this series, we’ve explored functionalism, reductionism, and eliminativism as possible ways to account for mental events as physical phenomena. But for many, these theories do not provide a satisfying answer. This is particularly true when it comes to trying to account for the specialness of our experiences and our sense of mental agency.

Enter non-reductive materialism.

This theory offers a different approach to the mind-body problem. It tries to explain our intuitions about consciousness within the scientific view of physicalism.

But does it succeed?

To find out, let's ask three questions:

What is non-reductive materialism?

Why might someone believe in non-reductive materialism? and,

What are the main arguments against non-reductive materialism?

Q1: What is non-reductive materialism?

The philosopher Donald Davidson is usually seen as the main thinker behind non-reductive materialism (his theory is called anomalous monism).

To answer the question — what is non-reductive materialism — we need to get our heads around two things:

the concept of supervenience and,

Davidson’s Three Principles

Let’s take these in turn.

What is Supervenience?

Supervenience is a technical term philosophers like to use when navigating tricky philosophical terrain.

Formally, it is defined as:

a relationship between two sets of properties where one set (A) supervenes on another set (B) if and only if there can be no difference in A without there being a difference in B.

Let’s unpack it.

At its core, supervenience is a way of describing how some properties depend on other properties.

Imagine an image of a piece of cake on your computer screen. This image depends on the arrangement of pixels that make up the image. The image of the cake cannot change (to say, an image of an umbrella) without changing some of the pixels. So, we say the image of the cake supervenes on the arrangement of the pixels because the image of the cake cannot change without there being a change in the pixels.

In the philosophy of mind, many philosophers, Davidson included, argue that the mind supervenes on the brain.

If you have a thought that it will rain today, this mental event is associated with a specific physical event in your brain, such as a particular pattern of neural activity. If your thought about rain suddenly changed to a thought about remembering your umbrella, there would necessarily be some corresponding change in your brain's neural activity.

The Three Principles

In his classic 1970 paper Mental Events, Davidson outlines three principles. He argues that we intuitively believe all three of these principles to be true, even though they seem logically inconsistent.

Let’s review each principle, and then we’ll examine the potential contradiction.

Principle 1: Mental events can cause physical events.

Intuitively, we think that our beliefs and desires cause our actions. For example, my belief that it would rain today and my desire to stay dry caused me to grab my umbrella before leaving home.

Principle 2: all causal relationships are governed by strict, deterministic laws.

This is a universally accepted principle in physics.

We understand that physical events (like releasing a ball from a height) can cause other events to happen (like the ball falling to the ground). For this causal effect to happen, there must be a law-like regularity that connects the initial event (releasing the ball) with the proceeding event (the ball falling — in this case, it’s the law of gravity).

Principle 3: there are no psychophysical laws

When we think about why people do things, we don't usually break it down into strict cause-and-effect relationships, like we do with physics. Instead, we like to paint a bigger picture. We make sense of ourselves and others' behaviour by assuming that we think and make choices that are not strictly determined by physical processes.

So, while we might accept that physical events, like balls falling, are predictable based on strict deterministic laws, there doesn't seem to be a comparable set of laws that allow us to predict mental events (like thoughts and decisions) from physical events or vice versa.

The three principles seem to be logically inconsistent.

If I have a mental event, say a belief that it will rain today, that causes a physical act, say I grab an umbrella before leaving the house, then according to Principle 2, the causal relationship between my belief and my physical act must be governed by strict deterministic laws.

But! This would contradict Principle 3, which states that no such laws exist.

It seems we have a problem!

We can’t simultaneously uphold both Principle 1 and Principle 2 while maintaining Principle 3.

But Davidson thinks we can.

He claims we can have our Principle 3 and be physicalists, too.

He does this by claiming a special type of supervenience.

Davidson accepts supervenience — mental events can't change without a change in the brain's neural activity. But, he argues, that the supervenience relationship between the mental and the physical does not imply reducibility. In other words, while Davidson agrees there is a close relationship between the mind and the brain, he also claims the mind cannot be reduced to or fully explained by the brain.

Q2: Why might someone believe in non-reductive materialism?

One way to resolve the logical inconsistency of the Three Principles is to find a Principle that, when rejected, resolves the inconsistency.

Many physicalists would accept Principle 1 (mental events can cause physical events) and Principle 2 (all causal relationships are governed by strict, deterministic laws), as these align more closely with standard physicalist views.

It’s Principle 3 (there are no psychophysical laws) that physicalists will often question.

But Davidson argues that we should accept all three principles, including the potentially contentious Principle 3, and he offers three compelling reasons for doing so.

Folk Psychology

Davidson's first argument for accepting Principle 3 comes from our everyday understanding and use of mental concepts like beliefs, desires, and intentions. We discussed this everyday commonsense idea of mental concepts in the article on eliminative materialism — there, we referred to these concepts as folk psychology.

Davidson argues that while we might understand that a specific mental event is identical to a specific brain event, it does not follow that we could predict or explain mental events as a class — like beliefs, desires, and intentions.

So, in principle, science might (one day) be able to predict and explain the specific belief I had about rain at 9 AM this morning with the specific brain event I had at the same moment. But science can’t explain beliefs as a class or mental concept.

Our typical interest in folk psychology relates to classes or concepts like desires, habits, knowledge, and perceptions. We use these concepts to explain and predict behaviour. Davidson argues that science can't explain folk psychological concepts or reduce them to purely physical facts.

Free Will

Davidson's second argument for accepting Principle 3 relates to free will and human agency.

If mental events are governed by strict, deterministic laws in the same way that physical events are, it’s difficult to conceive of how human actions could ever be truly free. For instance, if every thought or decision could be perfectly predicted by knowing the exact state of our brain, it would be difficult to argue that we genuinely have free will.

By accepting Principle 3, Davidson leaves room for some unpredictability and spontaneity in mental events, which he sees as crucial for free will.

The Is-Ought Distinction

Davidson's third argument for accepting Principle 3 uses the is-ought distinction as an analogy.

The is-ought distinction, first pointed out by philosopher David Hume, says that we can't figure out what ought to happen simply by looking at what is.

Here's an example: Imagine a study that shows 90% of people jaywalk at a particular intersection. That's a fact about what is happening. But this fact alone doesn't tell us what ought to happen or what's right or wrong. We can't use only this information to decide if people ought to jaywalk or if the city ought to build a crosswalk. To make those 'ought' statements, we'd need additional moral reasoning or values.

Davidson applies this idea to the mind-body problem. In ethics, while facts can inform our moral judgments, we generally agree that we can't derive 'ought' statements purely from 'is' statements. We can't say jaywalking ought to be illegal just because we know jaywalking happens.

Davidson uses this widely accepted idea as an analogy. He suggests that, similarly, we can't fully explain or reduce mental concepts (like beliefs or decisions) to physical events in the brain, even if we believe mental events have a physical basis. Just as we can't get 'ought' from 'is', we can't get 'mind' entirely from 'brain'.

Q3: What are the main arguments against non-reductive materialism?

Non-reductive materialism faces several criticisms. But I want to focus on one argument from philosopher Jaegwon Kim.

To understand Kim’s argument, we need to understand one more term:

Overdetermination

Overdetermination occurs when an event is claimed to have more than one sufficient cause — a sufficient cause is a cause that, on its own, is enough to have the effect.

A classic example is a firing squad: if five shooters all accurately fire at a target simultaneously, and any one of their shots would have been sufficient to cause death, then the death is overdetermined. Each shot is a sufficient cause, yet they all occur together.

Overdetermination is typically found and accepted in thought experiments about moral events. But in physics, explaining events through overdetermination is generally considered to be a problem. This is because it violates the principle of parsimony (also known as Occam's Razor), which suggests that simpler explanations should be preferred over complex ones. It also challenges the idea of causal sufficiency — if one cause is truly sufficient, additional causes are, by definition, unnecessary.

In the case of the firing squad example, overdetermination is typically accepted because of moral and legal concerns: responsibility is distributed among all members of the firing squad, avoiding singling out any one individual as solely responsible for the death. This is a rare case where overdetermination is intuitively acceptable.

But in physics, it is generally accepted that every physical event that has a cause has no more than one sufficient physical cause. This claim is based on the principle of the causal closure of the physical domain. For example, consider a row of dominos falling. The physical event of each domino falling has a sufficient physical cause: the previous domino hitting it. We don't need any additional causes to explain the dominos falling.

Let's see how Kim uses overdetermination to challenge non-reductive materialism.

The Argument from Overdetermination

Kim argues that non-reductive materialism leads to a form of overdetermination that is typically considered to be a problem. Here's how the argument unfolds:

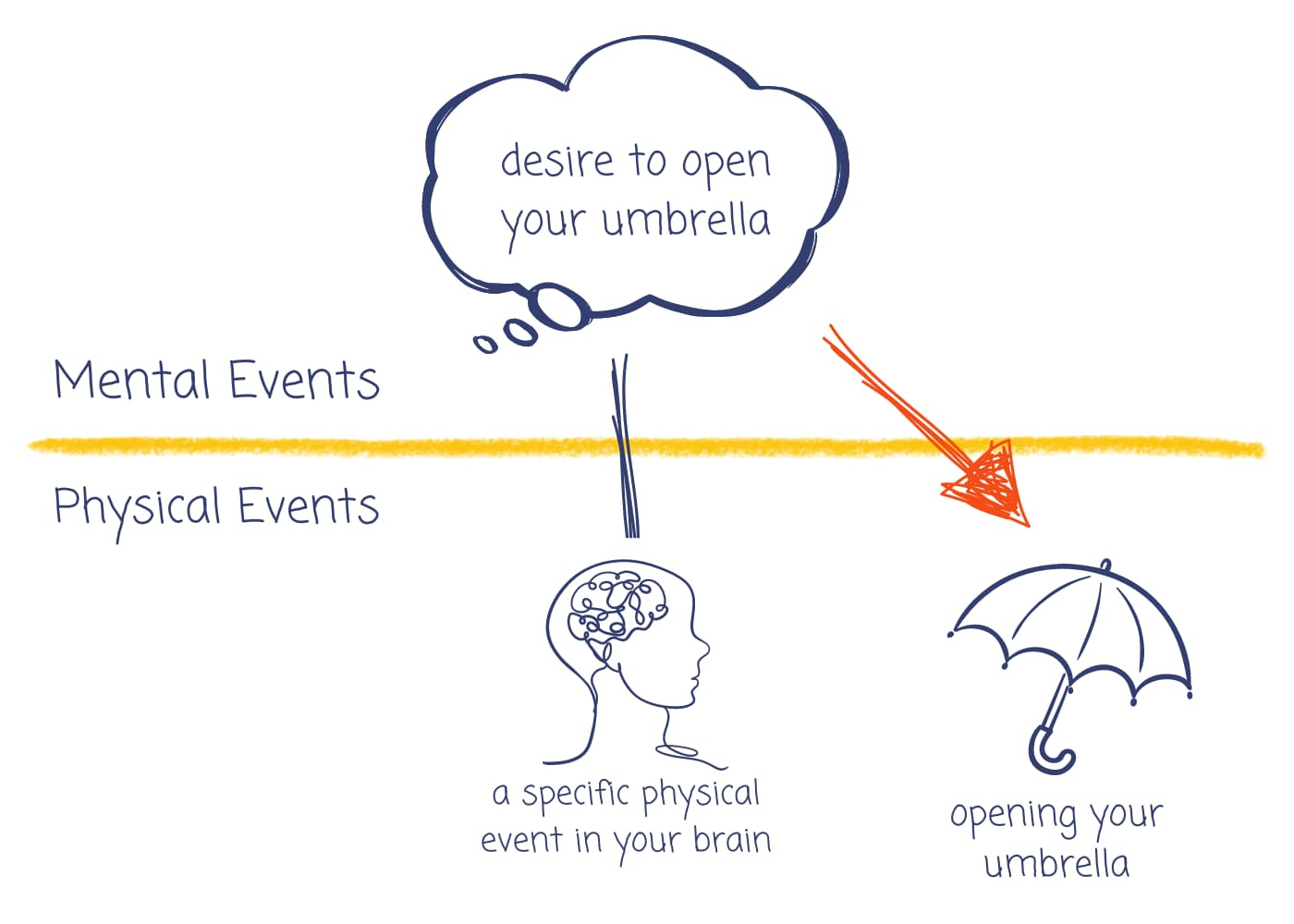

Let's suppose you have a specific mental event of the desire to open your umbrella. This mental event is associated with a specific physical event in your brain.

Now, let’s suppose your desire to open your umbrella causes the physical event of opening your umbrella.

According to the principle of the causal closure of the physical domain, because opening your umbrella is a physical event that has a cause, whatever caused you to open your umbrella must be a sufficient physical cause. We know that you opened your umbrella because of your desire to open your umbrella — so the sufficient physical cause would be the specific physical event in your brain associated with your desire to open your umbrella.

We have a problem!

The physical act of opening your umbrella is overdetermined — you have two allegedly sufficient causes for opening your umbrella: (1) the mental event of the desire to open your umbrella and (2) the specific physical event in your brain.

Given the causal closure of the physical, the specific physical event in your brain is sufficient to cause you to open your umbrella.

So, to resolve this, we must conclude that while the specific physical event in your brain is the ‘true’ cause of opening your umbrella, your desire to open your umbrella did not actually cause you to open your umbrella, despite appearances.

This renders your desire to open your umbrella causally useless — it appears to cause you to open your umbrella, but the real causal work is done entirely by the specific physical event in your brain.

Any mental event that appears to cause a physical event but actually has no causal power is the definition of an epiphenomenon.

So, do we accept epiphenomenalism?

Kim argues that’s one option. But there are two other options he thinks we could also consider.

The mental event of your desire to open your umbrella could be identical to the specific physical event in your brain.

This means we would accept reductive materialism — mental events can be fully explained by physical events.

Alternatively, if we accept that mental events don’t do anything, we might wish to reject the whole idea of mental events altogether. This would mean accepting eliminative materialism — mental events don’t exist.

So, Kim's argument, if we accept it, puts us in a tricky situation. Every time we try to accept non-reductive materialism, we end up with either epiphenomenalism, reductivism, or eliminativism. Kim's argument suggests that we can't have it both ways — we can’t have both a physically based theory and irreducibility — we must either reduce the mental to the physical, eliminate it altogether, or accept that it has no causal power.

Potential Consequences of Kim’s Argument

Kim's argument (again, if we choose to accept it) seems not just to challenge the logical coherence of non-reductive materialism, but it also raises questions about the very things that we mentioned in Question 2 that we might have intuitively found rather appealing.

What happens to our folk psychological concepts if we accept Kim's argument? Do things like beliefs, desires, and intentions become causally inert? If so, does this mean folk psychology loses its ability to explain and predict human behaviour — which is the very reason for asserting folk psychology in the first place?

And what about free will? Without a distinct mental level, how can beliefs, desires, and intentions have any genuine causal effects? Is there no room for free will? If so, how do we explain agency and moral responsibility?

What about the is-ought distinction? The analogy with the is-ought distinction becomes strained if we accept that the mental can be fully reduced or eliminated. So, if we question the analogy, should we also question the is-ought distinction itself?

Thank you.

I want to take a small moment to thank the lovely folks who have reached out to say hello and joined the conversation here on Substack.

If you'd like to do that, too, you can leave a comment, email me, or send me a direct message. I’d love to hear from you. If reaching out is not your thing, I completely understand. Of course, liking the article and subscribing to the newsletter also help the newsletter grow.

If you would like to support my work in more tangible ways, you do that in two ways:

You can become a paid subscriber

or you can support my coffee addiction through the “buy me a coffee” platform.

I want to personally thank those of you who have decided to financially support my work. Your support means the world to me. It's supporters like you who make my work possible. So thank you.

Great post! Your Substack is quickly becoming my go-to when I want a quick and clear breakdown of various terms in philosophy of mind.

I haven't read Davidson himself—my understanding of him comes almost exclusively through editing husband's book, which isn't on the same topic—and I appreciate learning what he had to say on the mind-body problem without having to read him myself. From what you've outlined here, he seems quite fair-minded.

I think since the issue we're dealing with here doesn't belong to the realm of science proper, we have every right to take a hard look at our now-impoverished notions of causality and consider what we lost when we dumped Aristotle's formal and final causes. Overdetermination only seems to be a problem if you insist on looking at the matter exclusively through a scientific lens (which is a philosophical position, not a scientific one), but I don't see it as a problem for those who believe knowledge is much broader than science's reach. (Gasp! Sacrilege!)

Thanks for the trip down memory lane! But those guys made big errors. What they call “epiphenomenalism” is just causation at different levels of description. For example, what caused WWI? The assassination of Franz Ferdinand? No. According to Kim the answer is particle physics. You see, the cause of WWI is over-determined, so the assassination was superfluous.

They thought there was such a thing as *the* cause. But every event has multiple causes at different levels of description.