Epiphenomenalism: Is Consciousness a By-Product?

The Five Most Controversial Ideas in the Study of Consciousness [Part 4]

This article may be cut off in your email. If so, you can find the complete article here.

Hello Curious Humans!

This week, we continue our series on The Five Most Controversial Ideas in the Study of Consciousness with Epiphenomenalism. Epiphenomenalism is not just a cool word to say; it’s also one of the most counterintuitive and provocative concepts in the philosophy of mind.

One of the main puzzles in the philosophy of mind is understanding the mind-body problem — how does the mind relate to the brain? How does consciousness — things like feelings and experiences — cause physical actions in the world? Epiphenomenalism challenges our everyday thinking — suggesting that consciousness doesn’t influence our physical actions at all.

This week in When Life Gives You AI, we’re asking three questions:

What is epiphenomenalism?

Why might someone believe in epiphenomenalism? and

What are the main arguments against epiphenomenalism?

This article is Part 4 in the series on The Five Most Controversial Ideas in the Study of Consciousness. It draws on Part 2, where I discuss René Descartes’s theory of Substance Dualism and the Interaction Problem. If you are unfamiliar with Descartes’s ideas, you may want to pause here and read Part 2 before diving into this one.

Part 1:

Part 2:

Part 3:

Question 1: What is Epiphenomenalism?

Epiphenomenalism is a more recent view of the philosophy of mind. Its main idea is that consciousness is merely a by-product. It is produced by the brain, but it has no influence whatsoever on the brain—or anything else.

The term made its debut back in 1890, introduced by William James in his hefty tome, The Principles of Psychology. In a chapter that might as well have been titled When Humans Act Like Robots, he mentioned the term epiphenomenalism — just once. His more favoured term for the same concept was automaton theory or the conscious automaton theory.

The related word epiphenomenon was originally a medical term from the late 19th century. It was used to describe symptoms that appear alongside a disease but don't actually contribute to it. Epiphenomenon is also used in other disciplines to describe a side effect or by-product; it's there, but it doesn’t cause the main event.

A famous example of an epiphenomenon comes from Thomas Huxley — the renowned biologist. Imagine a steam engine chugging along the countryside, with steam billowing out from its chimney. Atop the engine sits a whistle. When the engineer pulls a lever, the steam rushes through, and the whistle blares its high-pitched song. The sound of the whistle does not propel the engine forward. While the steam engine causes the whistle, the whistle does not affect the steam engine — it doesn't contribute to the engine's power or direction in any way. It's simply a by-product of the steam that's doing the work.

Huxley drew an analogy between our conscious experiences and the whistle of a steam engine. Huxley argued that just as the whistle sound is caused by the engine but does not, in turn, influence the engine, so too is it that our consciousness is caused by our brain but does not, in turn, influence our brain. It’s a one-way relationship.

Question 2: Why might someone believe in epiphenomenalism?

In Part 2 of this series, we discussed Descartes and his Meditations on First Philosophy. In the Meditations, Descartes develops his theory of substance dualism, claiming that the world is made of two substances: the non-physical mind and the physical world. But the biggest problem for Descartes is the interaction problem. How does the non-physical mind interact with the physical brain? How can any non-physical thing, like a mind that takes up no space and has no physical properties at all, affect the physical world?

Toward the end of Part 2 of this series, I mentioned two main ways to avoid the interaction problem in Descartes's theory. One way is to reject the dualistic separation between the mind and the body and claim there’s just one thing. This is called monism. In Part 3, we explored one form of monism: metaphysical solipsism, the view that everything that exists is the non-physical mind. Another form of monism is physicalism (which we haven’t discussed in depth yet), the view that everything that exists is physical.

I will discuss physicalism in much more depth in future articles, but for now, let’s review a famous thought experiment often used to highlight why someone might not find physicalism appealing.

Mary and her black-and-white room

Mary is a brilliant scientist who is, for whatever reason, forced to investigate the world from a black and white room via a black and white television monitor. She specialises in the neurophysiology of vision and acquires, let us suppose, all the physical information there is to obtain about what goes on when we see ripe tomatoes, or the sky, and use terms like “red”, “blue”, and so on. She discovers, for example, just which wave-length combinations from the sky stimulate the retina, and exactly how this produces via the central nervous system the contraction of the vocal chords and expulsion of air from the lungs that results in the uttering of the sentence “The sky is blue”…

What will happen when Mary is released from her black and white room or is given a colour television monitor? Will she learn anything or not? It seems just obvious that she will learn something about the world and our visual experience of it. But then it is inescapable that her previous knowledge was incomplete. But she had all the physical information. Ergo there is more to have than that, and Physicalism is false.

—Frank Jackson, in Epiphenomenal Qualia, 1982.

Many find epiphenomenalism resonates with their feeling that consciousness must be more than the physical. When Mary is released from her black-and-white room, it seems she would learn something new when she sees red for the first time. Because Mary currently knows everything physical about the world, what she will learn when she is released from the room and sees red for the first time must be facts that are not physical facts. So, what she will learn must be a non-physical fact.

People argue about what exactly this thought experiment tells us, but we'll leave that discussion for another day. For now, it’s enough to understand that for many, Jackson’s thought experiment points them back towards some form of dualism.

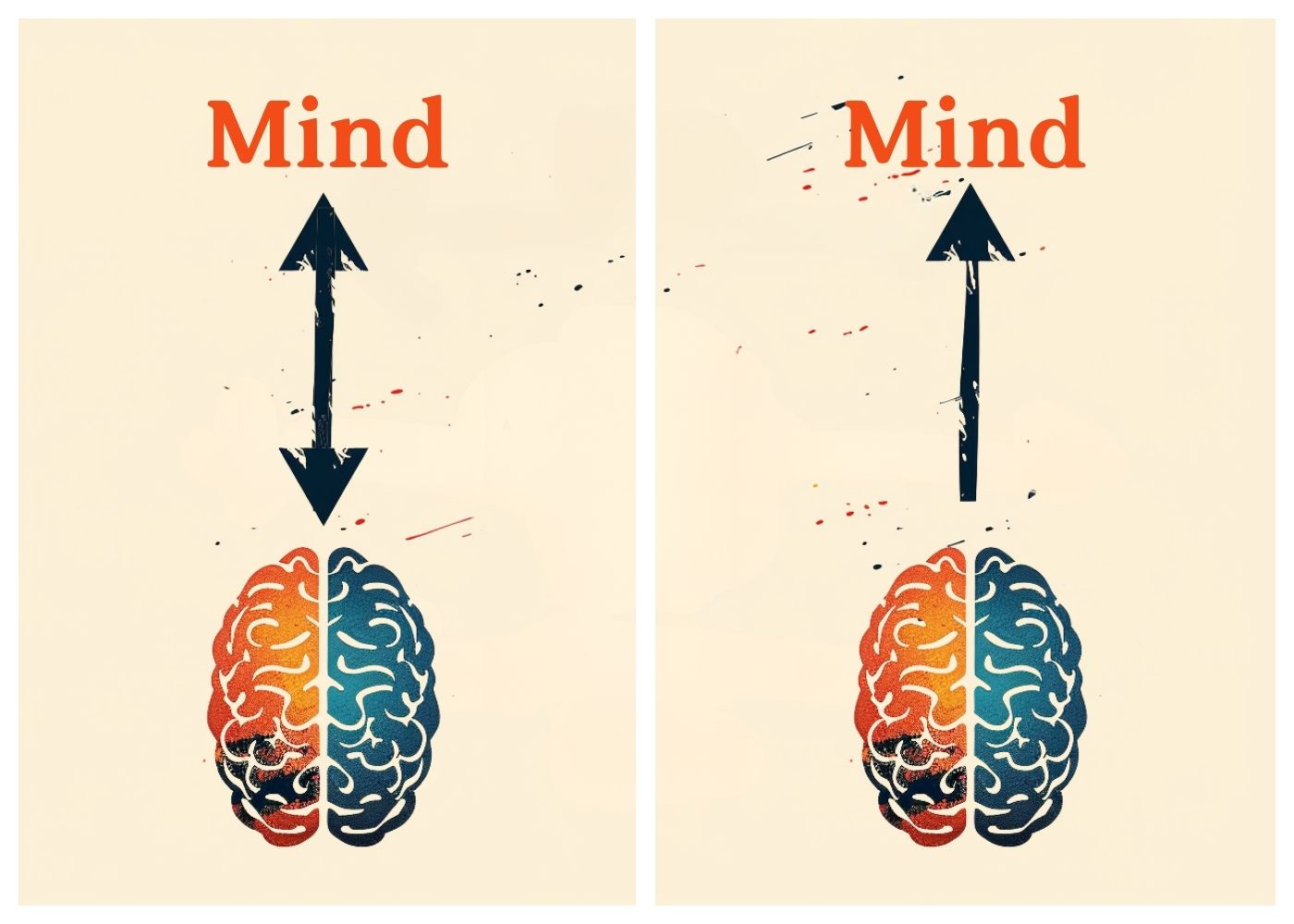

Finding Jackson's thought experiment about Mary compelling evidence for the existence of non-physical facts, yet also understanding the infamous interaction problem inherent in Descartes' substance dualism, some turn to the second way to avoid the interaction problem. They deny there’s an interaction at all. Epiphenomenalism provides a way to do just that. Where substance dualism says there is a two-way relationship between the brain and the mind (illustrated on the left in the image below), epiphenomenalism claims the relationship is one-way (right in the image below).

The causal closure of the physical

To understand the epiphenomanalist's claim, we need to review the principle of the causal closure of the physical, which is critical in the mind-body debate.

The idea of causal closure of the physical is that every physical event can be fully explained by preceding physical causes. This means that the physical universe is a closed system when it comes to causality; if you trace the cause of any physical event, you'll end up with another physical event, not something from outside the physical world.

For instance, think about a line of dominos. When one falls and knocks over the next one, the cause of each domino's fall is entirely physical—the push from the previous domino. There's no need to look for a non-physical explanation, like an ethereal spirit or an abstract idea, to explain why the dominos fall.

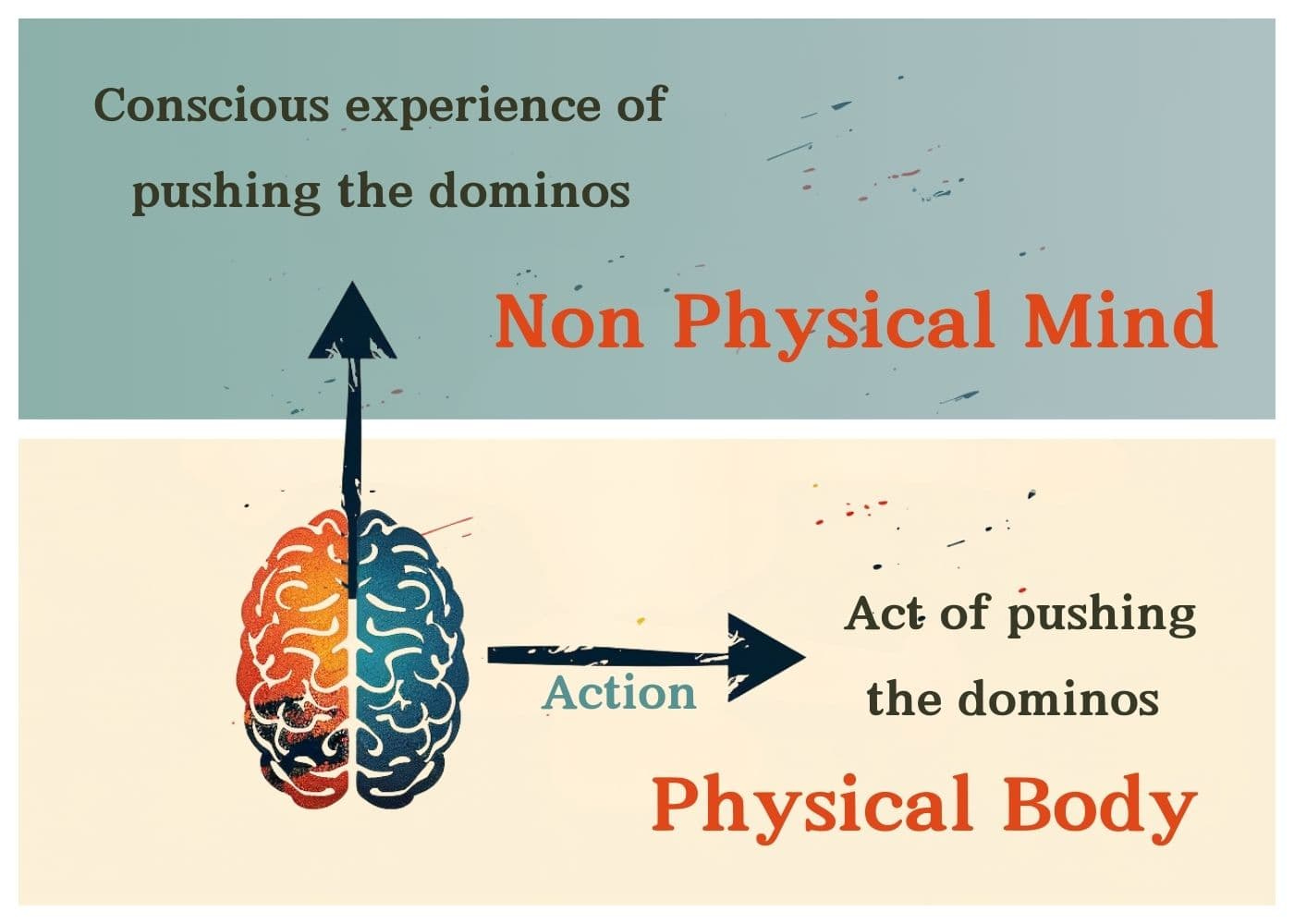

According to the causal closure of the physical principle, the domino falling must be caused by something physical — in this case, our brain and body. So, our brain forms a motor action that causes our arm to move towards the dominos, and our finger pushes the first domino (represented in the bottom section of the image above). According to epiphenomenalism, at the same time (or perhaps after), the brain must cause a conscious experience of pushing the first domino (represented in the top section of the image above). The conscious experience of pushing the dominos is a by-product of our brain, not the cause of the action itself.

Question 3: What are the main arguments against epiphenomenalism?

The consequences of epiphenomenalism are pretty wild. Perhaps for that reason, there are several arguments against epiphenomenalism. Let’s focus on just three. The first argument challenges common thinking, the second provides empirical evidence against epiphenomenalism, and the third challenges the logic underlying this view.

1. No free will and no agency

One of the first things to note about epiphenomenalism is the consequence such a view has on our everyday notions of free will and agency. If our consciousness—the reasons we think we do things — doesn't actually cause our actions, then what is consciousness for? This raises the unsettling question of whether we truly have free will and agency over our decisions. Instead, it suggests that our sense of being a conscious decision-maker is, in fact, an illusion. Our actions are determined by unconscious brain processes beyond our conscious control.

According to epiphenomenalism, when you reach for that cookie in the cookie jar, it’s not because you want a cookie. Nope. Your thoughts and wants have nothing to do with it. Your wanting to have a cookie is just an afterthought, a narrative your brain spins up to explain your actions.

If our consciousness, with all its intentions, desires, and decisions, doesn't drive our actions but merely narrates them after the fact, then the idea of free will and agency as we traditionally understand it starts to look shaky. It suggests that we're not genuinely choosing in the way many think we are; instead, our actions are simply the result of our brain processes. In this light, our consciousness is not the director of our actions but the audience member watching them.

If epiphenomenalism is true, then consciousness has no work to do.

Some evidence seems to support the idea of no free will. The famous Libet experiments appear to demonstrate that brain activity associated with decisions occurs before people are consciously aware of making a choice. And the phenomenon of blindsight, where patients with damage to their primary visual cortex exhibit the ability to respond to visual stimuli without consciously perceiving them, suggests a disconnect between consciousness and physical responses. These examples raise the possibility that our subjective experience of making choices and initiating actions may simply be post-hoc explanations constructed by the brain rather than the a priori driver of our actions. What the Libet studies and blindsight tell us about consciousness is a contentious topic, which I will discuss in much more detail in future articles.

For some, the idea that we have no free will is too unsettling to take epiphenomenalism seriously. But even if you're at peace with the notion that free will is an illusion, two other rather thorny issues lurk in the corners of epiphenomenalism.

2. Placebo effects

Most people are probably familiar with the concept of the placebo effect, but just in case you need a refresher, here's how it works: a placebo effect occurs when a person experiences a real physiological response after being given sham treatment that should have no effects. The physiological response occurs simply because the person believes they have received a treatment that does have physiological effects.

For example, in a study looking at the effects of a new drug for hypertension, half of the participants are given the drug (drug group) while the other half are given a sugar pill, which has no active therapeutic ingredients (placebo group). Crucially, the participants are unaware of which group they have been randomly assigned to. The placebo effect can occur when people in the placebo group experience changes they believe to be because of the actual drug. Despite taking a sugar pill, some in the placebo group show reduced heart rate, lower blood pressure readings, and other measurable physiological changes simply because they expect the "medicine" to have such effects. Their belief and expectation that the drug will have an effect results in actual physical changes in line with their expectations, even though they didn’t actually take the drug.

The placebo effect challenges epiphenomenalism because it suggests that our conscious beliefs and expectations can influence our physical body. If conscious experiences were truly epiphenomenal with no causal powers, we would expect that our thoughts would have no measurable influence on our physical biology. The fact that placebo effects happen, sometimes quite significantly, is evidence that our consciousness has physical effects.

3. No effects means no effects. Always.

The fact that I am writing an article about consciousness suggests that consciousness affects my physical brain. Writing is a physical event. How can I write about consciousness if it has no effect on my physical brain? Yet, here you are, reading or listening to this article about consciousness.

To say, “I feel that I am conscious,” I must use my physical body. I must engage my vocal cords, articulate my mouth, and push air through my lungs to produce the sounds that represent the idea that I believe I am conscious. So, my physical body must produce sounds that represent my belief that I am conscious. Yet, according to epiphenomenalism, these vocal sounds cannot be caused by my consciousness because my consciousness has no physical effects. The utterance, ‘I feel that I am conscious’, can only be caused by my physical body. In this framework, my non-physical consciousness is mute—it cannot directly influence my physical actions or communicate its presence. It exists in silence, unable to tell my physical body of its existence or its experiences.

This presents a paradox: If I say, “I feel that I am conscious,” one thing you can know for sure is that I couldn’t be saying this because I was conscious. If consciousness is an epiphenomenon, it wouldn’t be causing our bodies to say it. That would be a contradiction.

When Huxley claims that consciousness is to the brain as the sound of a steam whistle is to the steam engine. He claims that the steam whistle has no effect on the steam engine, and this is true. But the analogy doesn’t quite work. Huxley wants to claim that consciousness is to the physical world as the steam whistle is to the physical world. But this is just not true. The steam whistle does have effects on the physical world. It causes sound. According to epiphenomenalism, consciousness has no physical effects — it does not cause anything.

So we are left with a non-physical mind that not only lacks free will and agency but is also effectively in a locked-in state, utterly detached from the physical and having no effect at all. It does not influence anything.

Some might argue that they still feel they detect a non-physical mind. But even this assertion, if it were true, the act of saying that they detect their consciousness must be an effect of them detecting their consciousness, which is an effect of the epiphenomenon, which is ruled out by definition.

The Sum Up

Epiphenomenalism is one of the more counterintuitive perspectives on consciousness — stripping it of all its power. While some find it potentially resolves the interaction problem inherent in Descartes’s view, it comes with other challenges.

What are your thoughts on an epiphenomenal account of consciousness? Does it resonate with your understanding of the mind-body relationship, or does it raise too many issues to take seriously? I’d love to know your thoughts.

Thanks so much for reading this article.

I want to take a small moment to thank the lovely folks who have reached out to say hello and have joined in the conversation here on Substack.

If you'd like to do that, too, you can leave a comment, email me, or send me a direct message. I’d love to hear from you. If reaching out is not your thing, I completely understand. Of course, liking the article and subscribing to the newsletter also help the newsletter grow.

If you would like to support my work in more tangible ways, you do that in two ways:

You can become a paid subscriber

or you can support my coffee addiction through the “buy me a coffee” platform.

I want to personally thank those of you who have decided to financially support my work. Your support means the world to me. It's supporters like you who make my work possible. So thank you.

Three articles that got me thinking this week:

By:

By

By

I always found it hard to see what epiphenomenalism added to reductionism, from strong identity theories to weaker supervenience accounts, or Davidson's thing with anomalous monism.

You "explain' conscious experience, sort of, but it doesn't do anything, and without any sort of casual interactions it's hard to see that accounting for anything worth caring about.

Even eliminativism is more consistent. It's hard to defend in other ways, but at least it takes its physicalist commitments seriously.

The problem I think is less to do with finding the right theory of consciousness and more to do with asking why subjectivity is such a puzzle -- and why we believe we'll solve it with the same basic methods that got us into it (those being Cartesianism and empiricism).

My model of consciousness is based on what I learned in `The Mind Illuminated: A Complete Meditation Guide Integrating Buddhist Wisdom and Brain Science` by Culadasa (AKA Dr John Charles Yates PhD).

The mind is recursive in its processing. The physical senses process inputs subconsciously and filter out the useful bits and present it to your consciousness. Your consciousness is to be seen as a board room where all parts of the mind connect and share notes. Until the experience bubbles up into the board room, each thought is isolated. But it becomes known to the entire mind only once you think it.

There are various subsystems for your awareness. When you focus on something, most people think of that focus as themself and it feels like a camera. As your attention jumps from place to place, it's almost like a spotlight. That's the first part of awareness.

The second part of awareness is more diffuse. It's your peripheral vision, so to speak. When the five senses bring something into mind, or when your own thinking mind (or perhaps planning mind) comes up with a memory or an idea, then your peripheral awareness hears about it. But so do all your other senses. If you notice a bird chirping, it might influence your sight or smell. If you hear a sound, it might be danger and your mind recruits your other senses to confirm it.

And the last part of awareness is what I'd like to call the director. You might be working on something and intently focused on it, when suddenly you're distracted. Your attention shifts. You see or hear a notification on your cellphone, you hear the doorbell, anything that your director deems important or more interesting.

When you meditate, you're practising the art of focus. You're training your director to prevent it from shifting focus away from your breath or meditation object. When a thought pops up, you don't drift away from the breath. Instead, you may hold that thought in your peripheral awareness while staying focused on the breath.

Consciousness therefore is the interplay between your priorities for focus and awareness. You only become aware of external senses or stray thoughts when your subconscious doesn't know what to do with that input, or feels that it is important for you to become aware of it.

Combine this with the work of Dr Lisa Feldman Barrett. She thinks that your mind is a neural network and it simply has the job of predicting the future. All emotions are your mind deciding what to do with a possible upcoming event and creating an energy model to help you navigate that event.

For example, let's take anger. Someone gives you bad news and you feel the emotion bubble up. If you're a man and someone has threatened you somehow, you might get lots of energy and prepare to fight. The same man on another day while sick won't have the same response because he doesn't have the energy requirements. The same situation with a small woman facing dangerous odds will still become angry, but she might seethe quietly and plot revenge.

Same situation, different parameters, different energy requirements, different needs and solutions.

Emotions are then perceived by the mind and categorised according to what they feel like. Depending on your own emotional skills, your consciousness will interpret those signals differently.

For example, In both excitement and fear, you get adrenaline spiking. They both have the same chemical profile but the mental difference is in interpretation.