The Homunculus Fallacy and the Infinite Regress

The Five Most Controversial Ideas in the Study of Consciousness [Part 1]

Hello Curious Humans!

Back in the 18th century — before we knew about chromosomes and DNA and all the other important things — scientists had some pretty weird ideas about how human beings were made.

During this time, the microscope was staging a revolution in the sciences. Scholars were fascinated with the miniature and the microscopic—those elusive things hidden from the naked eye. Many hours were spent pondering the mysteries that might be revealed by the magnifying lens.

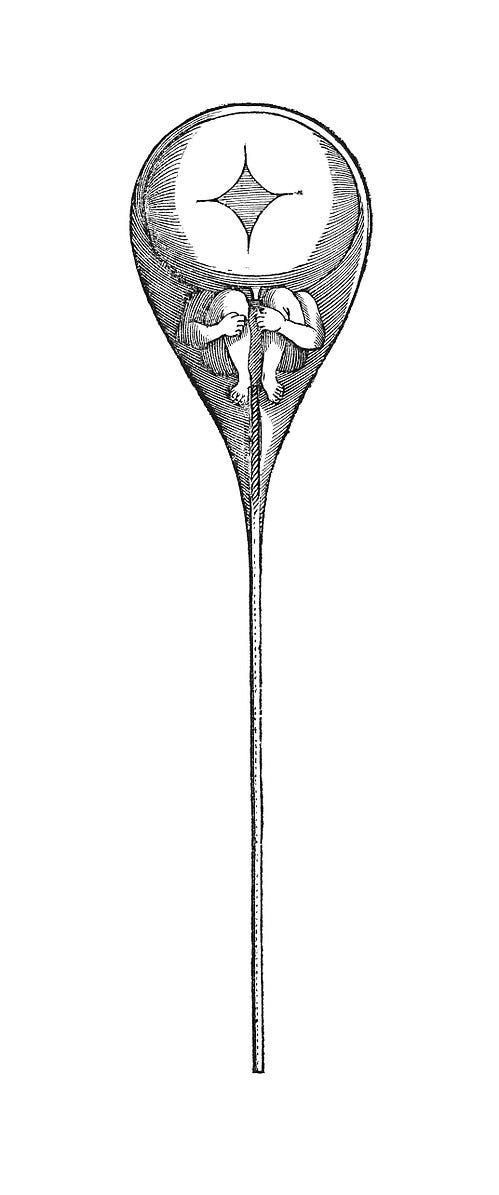

It was in this setting that Nicolaas Hartsoeker — a Dutch mathematician and physicist — included a peculiar drawing in one of his published essays.

It was a drawing of a sperm cell. He was trying to capture his idea of what a sperm cell might look like under a microscope. In the head of the sperm cell, he drew a tiny, preformed human being (see Figure 1). And he referred to this preformed human being as a homunculus (which is Latin for little man).

This week in When Life Gives You AI, we begin a short series dedicated to The Five Most Controversial Ideas in the Study of Consciousness. Welcome to Part 1, where we discuss:

The Homunculus Fallacy

An argument that tries to explain a thing with the very thing that it is trying to explain, resulting in an infinite regress.

Explanations for complex things — like consciousness — are often annoyingly vague and hand-wavey. They rely on misdirection and bad forms of reasoning to provide a sense of explanation — but look closely, and we find that no explanation is actually being given.

The Homunculus Fallacy is a good example of bad hand-wavey reasoning. Learning how to spot this fallacy can help us avoid being misled by such superficial arguments.

So, in this week’s issue of When Life Gives You AI, we’re asking:

What is an infinite regress?

Why is an infinite regress an unsatisfactory explanation?

How do we spot an infinite regress in our theories of consciousness?

How do we get out of infinity? and

Is the homunculus always a fallacy?

Let's dive in!

1. What is an Infinite Regress?

The concept of tiny humans existing inside sperm cells did not originate with Nicolaas Hartsoeker. It was an idea linked to a larger idea that was circulating during this time, called preformationism. Preformationism is the idea that every living being is fully formed in miniature before conception. And this fully formed miniature being lives inside sperm (or eggs, in some variants). Pregnancy, according to this view, is not about forming new structures; it is about enlarging what is already formed.

At the time, the idea that a fully formed, miniature human would grow into a baby might have seemed as plausible as any other theory. But with our current scientific understanding of DNA, cell division, and embryonic development, this idea seems rather ridiculous. But it’s not just ridiculous because it lacks scientific knowledge. There is a logical flaw in the theory.

This logical flaw has been dubbed the homunculus fallacy, and its structure goes something like this:

X needs to be explained

Reason Y is given to explain X

Reason Y depends on X

Let’s expand on this structure:

X needs to be explained: The development and growth of a human being from conception onward needs to be explained.

Reason Y is given to explain X: Preformationism provided an explanation — inside the sperm or egg, there exists a homunculus—a fully formed, miniature human being. So, a fully grown human is simply an enlarged version of its miniature form that originated in the sperm or egg cell.

Reason Y depends on X: But, we might ask, where did the homunculus come from? For reason Y (there’s a homunculus within the sperm or egg) to be true, the homunculus (H1) must have grown from an even tinier homunculus (H2) inside the sperm or egg of its parent. But, then, we would need an even tinier homunculus (H3) inside H2. For each homunculus, there must be a tinier fully formed homunculus to account for its existence.

2. Why is an infinite regress an unsatisfactory explanation?

The homunculus argument is logically flawed because it leads to an infinite regression that fails to provide a true explanation. It merely pushes the problem further back with each iteration and never addresses the original question. It's an endless loop — an unresolved chain of explanations, each depending on a prior one without a definitive endpoint.

Infinite regress arguments can make us feel like an explanation has been given — but on closer examination, we realise that nothing is actually being explained.

One of my favourite examples of an infinite regress comes from Steven Hawking. This is how he starts A Brief History of Time:

A well-known scientist (some say it was Bertrand Russell) once gave a public lecture on astronomy. He described how the earth orbits around the sun and how the sun, in turn, orbits around the center of a vast collection of stars called our galaxy. At the end of the lecture, a little old lady at the back of the room got up and said: “What you have told us is rubbish. The world is really a flat plate supported on the back of a giant tortoise.” The scientist gave a superior smile before replying, “What is the tortoise standing on?” “You’re very clever, young man, very clever,” said the old lady. “But it’s turtles all the way down!”

Steven Hawking so cleverly introduces the idea of an infinite regress — where the answer to a question raises another similar question. It’s a humorous reminder of the limits of certain explanations.

X needs to be explained: The Earth needs to be supported by something. What is it supported by?

Reason Y is given to explain X: The old lady gives the answer — the Earth is a flat plate supported on the back of a giant tortoise.

Reason Y depends on X: But the reason given demands its own explanation — what supports the tortoise? — creating an endless loop between question and answer — with no endpoint.

3. How do we spot an infinite regress in our theories?

In the examples given so far, spotting the infinite regress has been pretty easy. This is probably because we know enough about embryo development and astrophysics to spot them. Spotting an infinite regress on topics we don’t have a clear handle on might be a bit trickier.

A common view of consciousness is that there’s something like a movie that plays in our heads. And we are observers who experience the movie that our brain or mind provides us. Indeed, we might hear prominent scientists and philosophers describe consciousness in this way. They liken consciousness to an incredibly immersive, multi-sensory film unfolding within our minds — an internal cinema that gives us a 3D visual spectacle with surround sound, as well as scent, taste, touch, emotions and memories. And we are the only audience member of this 3D movie.

But if I am a little audience member sitting in my brain watching this 3D movie, then to see the movie, I would need another audience member inside the little audience member looking at the 3D movie that the first little audience member sees. And so on, and so on — an infinite number of little audience members, like Russian dolls, and I still haven’t explained how I have conscious experiences.

Let’s tie this to our logical structure as we did above:

X needs to be explained: There needs to be an explanation for how we have conscious experiences.

Reason Y is given to explain X: We have conscious experiences because we have a 3D movie playing in our head — an immersive, multi-sensory narrative that includes all perceptions, emotions, and thoughts, and we are the observer who watches this movie.

Reason Y depends on X: The reason given demands its own explanation, though. How does the observer — the one watching this 3D movie — have conscious experiences? There must be a 3D movie in the observer’s mind. But who is observing the movie in the observer’s mind? It demands a series of nested observers, each observer requiring its own 3D movie. The explanation of consciousness is perpetually deferred to another observer.

This theatre model of the mind assumes a type of conscious homunculus witnessing the 3D movie. Metaphorically, of course. I don’t believe people go around thinking we literally have a little human inside the head. But I imagine that for most people, there's a sense that there’s a ‘me’, and separate from the ‘me’, there are the experiences that the “me” watches come and go, like scenes on a movie screen.

When we’re examining a theory of consciousness, if the theory separates the observer from a centralised experience — we could have an infinite regress lurking about, and we should probably question further.

An Example for Pondering

An interesting argument to ponder is whether Descartes, the well-known philosopher from the 17th century, commits the homunculus fallacy in his theory of consciousness. In The Passions of the Soul, Descartes suggests that a person is a ghostly soul and the pineal gland is the “place in which all our thoughts are formed”.

Is Descartes committing a homunculus fallacy here? We might question how the ghostly soul is able to see the images in the pineal gland. Does the ghostly soul need a smaller ghostly soul inside the first one to observe the images on its pineal gland? Or does the ghostly soul's non-material nature mean the fallacy doesn't hold?

4. How do you get out of infinity?

The main problem with the homunculus fallacy is that it leads to an infinite regress. To get out of the infinite regress, we must break the chain — we must find a solid stopping point.

We could end the infinite regress early — before it even begins. Instead of attributing consciousness to a distinct "me" or “self”, we could reject the idea of a separate “self” altogether — there are just experiences. This approach would also need to rid itself of the centralised 3D movie theatre where experiences are supposedly unified because such a theatre would imply an observer. But this idea brings up a whole bunch of other issues, so we’ll leave that topic for another day.

A different strategy has been suggested by some philosophers. Instead of conceiving consciousness as a fully capable whole, we should conceive of it as a hierarchy of simpler and simpler parts. The key to this idea is that the parts lower in the hierarchy perform simpler tasks than those above it. Eventually, we will reach a level where the tasks are so simple that they can be explained by mechanical processes.

This is essentially how Daniel Dennett avoids an infinite regress in his theory of consciousness. He ensures that, at the most basic level, the parts are not conscious “agents” requiring further explanation but are instead simple, explainable processes.

Of course, not everyone agrees with this idea. Daniel Dennett has been accused of oversimplifying consciousness — failing to account for our rich, subjective experience.

5. Is the homunculus always a fallacy?

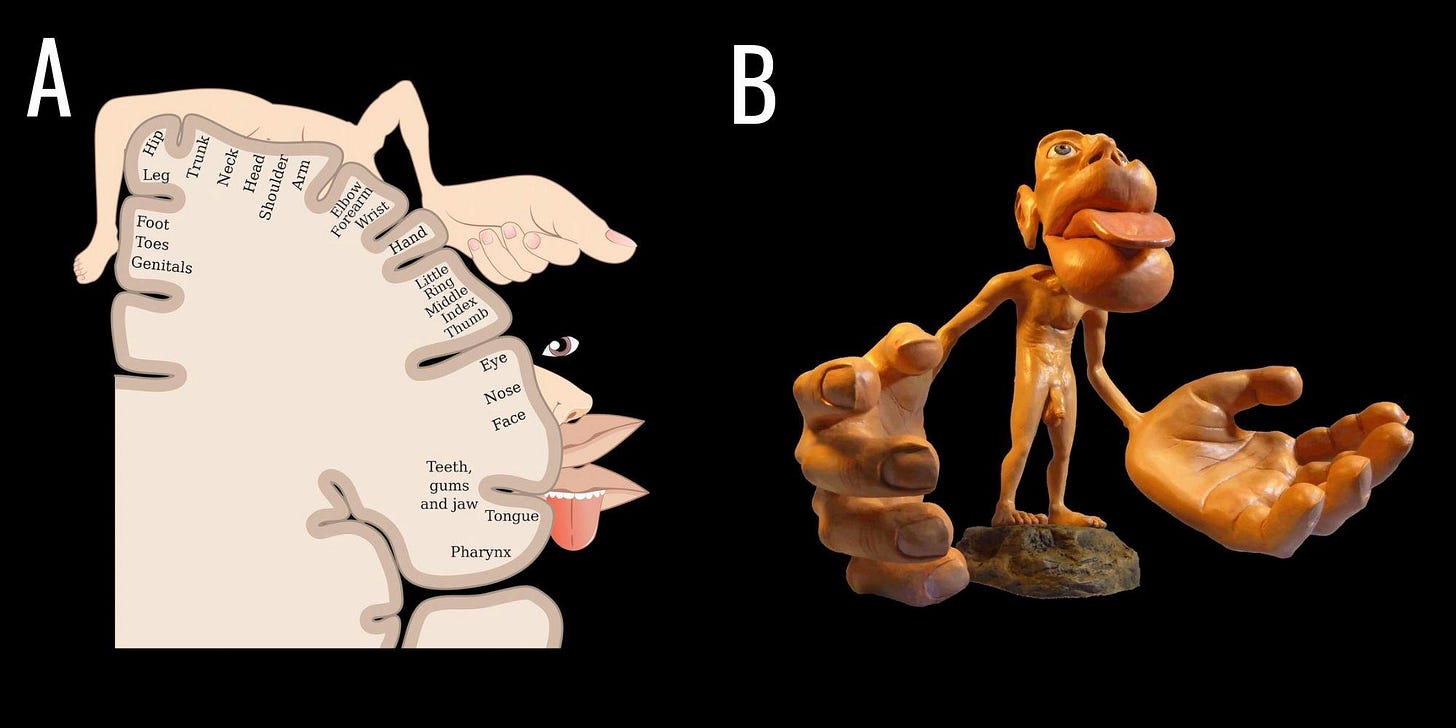

If you’re a Dungeons and Dragons fan, all this talk of homunculi has probably got you thinking about spell-casters and spy servants. And if you’ve studied any psychology, it has probably got you thinking about the hideous-looking creature in Figure 2B. This freaky-looking thing is really a map of the primary motor cortex and the somatosensory cortex in our brains.

This distorted homunculus illustrates how different body parts are mapped to the motor cortex and somatosensory cortex of the brain (see Figure 2A). The size of each body part in the homunculus corresponds to the amount of brain area devoted to it. For instance, the hands and face occupy disproportionately large areas because a larger part of the brain is devoted to fine motor control and sensory input from these body parts. Yeah, those hands are huge!

Some might wonder whether psychologists commit a homunculus fallacy when they describe the brain this way. But rest assured; there’s no infinite regress here. The psychologists aren’t claiming that the homunculus is watching sensations — there’s no separation between the observer and the experience. It’s just a visual tool — a map of sorts.

The Sum Up

But hang on a minute! I hear you say. If there’s no observer —no self — and no centralised 3D movie, why does it feel like there is? What does it mean to have a sense of self — heck! — what does it mean to have experiences?

Ah, consciousness! Simultaneously the most familiar and most mysterious of things.

I include the Homunculus Fallacy in the top 5 most controversial ideas — not just because of the fallacy itself but — because of what it represents. It is a fallacy — we want to avoid committing it. But what do we replace it with? Every time we discuss consciousness, we so easily fall into the pattern of explaining it in terms of an observer and its experience. The challenge is to find a way to explain consciousness without committing logical fallacies or resorting to other hand-wavey explanations.

Bonus Thoughts

on what the homunculus fallacy might mean for AI

Above, I mentioned a way to get out of the infinite regress by proposing a hierarchy of parts, where lower levels of the hierarchy perform simpler tasks than parts higher in the hierarchy.

This idea bears a striking similarity to the architecture of an artificial neural network. In a neural network, each layer works with a different level of detail, starting from simple patterns at the beginning and moving towards more complex ones as the data progresses through the layers.

John Searle, a philosopher sceptical about the possibility of conscious computers, argues that the homunculus problem doesn't apply to computers. In his view, humans are the external observers (ie. the homunculus) who experience computer outputs. However, if we consider the brain akin to a digital computer, as suggested by computational functionalists, a question arises: In the absence of an external user, who or what performs the role of the observer within the brain?

Questions like these lead us to ponder the nature of consciousness and the concept of self in both humans and artificial intelligence. If the brain has no central user — it merely generates a sense of one — could a similar process happen for AI? Could a complex hierarchy of tasks lead to a sense of self?

We find ourselves at the core of an ongoing debate between functionalists—who believe that information processing systems could be conscious — and their critics, who believe that consciousness requires more than just computational complexity.

Some (but not all) critics in this latter group argue that unlike machines, which are purely physical, there is a duality to humans. We are both physical and non-physical. And this duality could never be replicated in a machine.

Next week in When Life Gives You AI, I’ll explore the idea of dualism — specifically substance dualism — examining its implications and its fundamental flaws.

You did it again, Suzi.

I haven't even heard of the homunculus fallacy before, and now I have at least a grasp of the concept after an enjoyable read.

I look forward to the dualism chapter.

In the meantime, I'm off to have nightmares about humans-within-humans-within-humans like trippy Matryoshka dolls. So thanks for that!

Brilliant piece. Further to it I would humbly point towards several essays by Raymond Tallis. I am looking forward to the next essay. Thank you, John.