Regular newsletter readers will be aware of my series on The Five Most Controversial Ideas in the Study of Consciousness. This article can be thought of as an extension of that series and the introduction to a new series on physicalism — the theory of consciousness accepted by almost all neuroscientists and most philosophers.

Physicalism has different types. Technically, not all physicalist views insist that a biological brain is required for consciousness. But let's start with biological brains because all physicalist views agree they can be the reason for conscious experiences (even though some views allow for non-biological systems, too).

Your brain is an amazing thing.

Your brain has about 86 billion neurons. Each neuron, on average, has about 7,000 connections to other neurons. This means your brain has a total of about 600 trillion synaptic connections.

Large numbers like these are difficult to grasp, so let’s put it into perspective.

Imagine a pin-head-size chunk of your brain. Inside this pin-head-size chunk, there would be approximately 480 billion connections. In comparison, there are only 8 billion people living on the planet. So, in one pin-head-sized chunk of your brain, you have about 60 times more connections than there are humans living on the planet!

That is amazing. But is this what makes you — you? Are you simply billions of neurons and trillions of neuronal connections in a physical blob of white and grey biological matter?

This week we’re asking three questions:

What is physicalism?

Why might someone believe in physicalism?

What is the main objection to physicalism?

But first, two caveats:

There is a case to be made that physicalism and materialism are different theories of consciousness, but in this article, we will use the terms interchangeably.

Mental states is a term often thrown around when discussing physicalist theories. It’s an annoyingly vague term, I know! Writing a clear definition is tough because people disagree about what they are. So, for the purposes of this article, we will define mental states as the thoughts, feelings, perceptions, intentions, experiences, beliefs, desires, emotions, memories and all the other things you think about.

1. What is Physicalism?

There are many different versions of physicalism. But there are three (or four) main ones that I’ll focus on here. I will go into more detail about each view in some upcoming articles, but here’s a summary of the main views:

Identity Theory (aka Reductive Materialism)

The main claim of Identity Theory is that mental states are identical to brain states. When you have a thought or questioning feeling, that mental experience is literally just the firing of neurons and the physical brain being in a particular configuration at that moment.

That questioning thought you are having? It’s nothing but your brain in a particular state. Pain, pleasure, and thoughts are all brain states, no more, no less.

Functionalism

Functionalism, on the other hand, claims that mental states are more about what they do than what they are made of. A functionalist would say pain is not about where it happens in your brain but about its functions in avoiding bodily damage, learning from harmful stimuli, and motivating certain future behaviours.

Just like the function of telling time can be instantiated on different types of clocks — analog clocks made of gears, springs and pendulums, or digital clocks made of microcontrollers, LCD displays, and electronic oscillators — the function of consciousness could (at least theoretically) be instantiated in different types of machinery according to functionalism. As a functional property, consciousness doesn't necessarily need a biological brain; the functions associated with conscious experience could be performed by any system, biological or non-biological, as long as it satisfies the right functional roles.

Eliminative materialism

Eliminative materialists are the radicals of the group! They argue that mental states—concepts like thoughts, feelings, perceptions, intentions, experiences, beliefs, and desires—don't actually exist. Mental states are seen as fictitious constructs invented to provide an intuitive explanation. Eventually, these constructs will be understood as brain processes, and we will do away with the idea of mental states altogether. They will be the relics of an outdated psychology.

Non-reductive materialism

If eliminative materialists are the radical group, non-reductive materialists are the controversial group. Non-reductive materialists believe that while the mind is ultimately physical, mental states cannot be completely reduced to physical properties. The controversy is over whether such a view can be considered to be a physicalist view. While some claim it is, others argue it is really dualism in disguise. For this reason, non-reductive materialism has also been called naturalistic dualism, property dualism, and emergence theory.

2. Why might someone believe in physicalism?

Physicalism has arguably seen the most widespread acceptance and empirical support of all the philosophical theories attempting to explain consciousness. This is especially true in the neurosciences and cognitive sciences, but even among philosophers, physicalism is the most popular view. According to a recent survey, 56.5% of philosophers hold this view (27.1% were non-physicalists, and 16.4% held other views).

The success of physicalism is largely due to the vast evidence from neuroscientific research, which suggests that subjective experiences are highly correlated with observable physical changes and patterns of activity in the brain.

People put forward general lines of reasoning as evidence for physicalism, such as the success of physical sciences, the unity of the sciences (all sciences reduce to physics), and the causal closure of the physical (all physical events have physical causes). Instead of reiterating those ideas, in this article, let’s focus on some of the neuroscientific evidence that supports a physicalist view.

The developing brain

Babies are born with a fairly undeveloped brain. They have lots of neurons — about 100 billion of them. However, they have very few connections between those neurons. During the first year of life, a baby’s brain rapidly forms connections between neurons at an astonishing rate — more than 1 million new connections every second!

Initially, these connections are established in sensory areas, such as the visual and auditory cortices, allowing the baby to process sights and sounds. Next, language connections are formed, enabling the baby to comprehend and eventually acquire speech. Finally, connections associated with higher cognitive functions like reasoning, problem-solving, and decision-making begin to take shape.

These connections are not random. They are formed in response to experiences the baby encounters. Babies grow up in a variety of different worlds that are constantly changing. A baby that grows up in a small beach town in Australia will have vastly different experiences from a baby that grows up in the bustling city of Tokyo. Each baby’s brain will make connections appropriate for its world.

Consider what would happen if a baby were born in that small Australian beach town but immediately moved and was raised in the bustling city of Tokyo. The baby’s brain would develop in a way that is more akin to other babies raised in Tokyo than it would to Australian baby brains.

The adult brain

The brain is incredibly plastic. Even during adulthood. Connections are pruned and remodelled, strengthening some while eliminating others, gradually customizing its circuitry to fit its environment. This remarkable adaptability allows our brains to thrive in whatever surroundings they find themselves in.

If you decided to take up piano lessons, the area in your motor cortex that represents your fingers would become larger than mine (I don’t play the piano). And if you decided to become a taxi driver in London and learn ‘the knowledge, ’ your posterior hippocampi would become larger than mine.

Your brain changes according to what’s important. It adjusts and changes its connections to do what it needs to do. Do something you already know how to do, and your brain will not be very active. But try something new, especially something challenging, and your brain will look like it’s in overdrive while you figure it out.

So far, we’ve reviewed evidence that the environment and behaviour affect the physical structure of our brains. What about the opposite relationship? What evidence do we have that the brain's structure affects our behaviour?

Brain injury

We have a lot of evidence that damage to certain brain areas causes specific changes in behaviour, cognitive abilities, and conscious experiences. For example, damage to the visual cortex in the occipital lobe can lead to partial or complete blindness. Injuries to Broca's or Wernicke's area will affect language production or comprehension. Lesions in the hippocampus can devastate memory.

But, possibly the most famous case of brain injury causing changes was damage to the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in planning, decision-making, personality, judgment, impulse control, and even fundamental aspects of an individual's persona.

It was 1848. A 25-year-old construction foreman named Phineas Gage was working on a railroad construction project in Cavendish, Vermont. While setting explosive charges to clear rock for the construction project, a premature blast drove a three-foot-long, iron tamping rod straight through Gage's left cheek, behind his eye socket, and out the top of his skull, obliterating a significant portion of his brain's frontal lobe.

Miraculously, Gage survived the accident, but his personality and behaviour underwent a dramatic transformation. The once well-mannered, dependable Gage became capricious, profane, and lacked restraint and social awareness.

Drug effects

It's not only permanent physical brain injury that can have a significant altering effect on conscious experience. Chemical influences from certain drugs can have similarly dramatic effects. Psychoactive drugs like LSD, psilocybin, MDMA, and ketamine offer compelling evidence that our subjective experiences are linked to our brain's neurochemistry.

Similarly, stimulants and depressants can dramatically alter not just our outward behaviour but also our innermost qualitative experiences — our moods, perceptions, thought patterns, and sense of self.

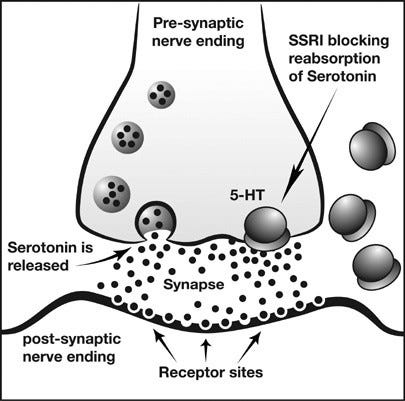

For instance, reuptake inhibitors like SSRI antidepressants modulate serotonin levels. They do this by blocking serotonin reuptake in the synapse so that the serotonin stays in the synapse for longer, stimulating the postsynaptic cell. This seemingly simple trick of ensuring a neurotransmitter continues to stimulate the post-synaptic cell is a useful way to influence mood, cognition, and behaviour. And it is further evidence for the idea that consciousness has something to do with the brain.

Even for those who subscribe to a non-physicalist view of consciousness, where consciousness is seen as non-material, the undeniable dependency of conscious experience on the brain cannot be ignored.

3. What is the main objection to physicalism?

There are a number of objections to physicalism. Some of them are specific to the different types of physicalism. For example, Leibniz's Law — the law that states that if two entities share all the same properties, they are identical — is usually raised in objection to Identity Theory. The argument is that mental states and brain states have different properties, so they cannot be identical according to Leibniz's Law.

And the argument from introspection — the argument that mental states don't feel like brain states when we introspect or examine our subjective experience — is often raised in objection to eliminative materialism. The idea is that our conscious experiences, such as feeling pain or seeing a colour, seem fundamentally different from the objective, physical processes occurring in the brain, making it difficult to eliminate or reduce mental states to purely physical brain states.

But let’s leave these objections for when we explore each theory in more depth. For now, I want to focus on the one seemingly insurmountable objection that all materialists must face.

The hard problem of consciousness

When it comes to physicalism, there seems to be a gap. An explanatory gap. Critics argue that we can study the workings of the brain all we want, but understanding neurons, neurotransmitters, neural networks, or even brain oscillations will not give us a satisfactory explanation of how we have subjective, phenomenal, conscious experiences.

These critics claim that it doesn't matter how much you look in the brain and at what level of abstraction — you won't find the essence of redness, the visceral feeling of anger, or the qualitative nature of consciousness itself.

The hard problem of consciousness was coined by the Australian philosopher David Chalmers. Chalmers argues that all the facts we outline above about the brain’s processes, mechanisms, and behaviours do not lead to facts about conscious experience. Chalmers agrees—the brain is involved in consciousness. We can explain the brain’s processes—that is the easy problem. The hard problem is answering the question of why these brain processes, mechanisms, and behaviours feel the particular way that they do or why they have any feeling at all.

Each of the different materialist views has a different answer to the hard problem. Here’s a quick summary:

Reductive Materialism claims consciousness can be accounted for by sensory equipment. For example, a conscious experience of fear can be explained by the sensations in one's body (e.g. increased heart rate, sweating, muscle tension).

Functionalism claims that consciousness is simply certain functional features of the brain. Pain, for example, is just a brain state with certain inputs (e.g. body damage), outputs (wincing) and other functions (flight, fight, or avoidance). Any state in any physical system (not necessarily a biological brain) that sets up this state would count as pain.

Eliminative Materialism responds to the hard problem of consciousness by saying that the feeling of what it is like is a kind of myth that science should not take seriously.

Non-reductive materialists can vary in their answer to the hard problem, but they tend to claim some form of emergence — the brain is greater than the sum of its parts.

These answers to the hard problem might seem unsatisfying. But given their popularity among those who study consciousness for a living, it’s worth considering these theories. So, we will explore them in greater depth in this series on physicalism.

Thanks so much for reading this article.

I want to take a small moment to thank the lovely folks who have reached out to say hello and joined the conversation here on Substack.

If you'd like to do that, too, you can leave a comment, email me, or send me a direct message. I’d love to hear from you. If reaching out is not your thing, I completely understand. Of course, liking the article and subscribing to the newsletter also help the newsletter grow.

If you would like to support my work in more tangible ways, you do that in two ways:

You can become a paid subscriber

or you can support my coffee addiction through the “buy me a coffee” platform.

I want to personally thank those of you who have decided to financially support my work. Your support means the world to me. It's supporters like you who make my work possible. So thank you.

![Functionalism: The Mind is What the Brain Does. [Part 1]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!gQE6!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe72e52bb-22e1-41c7-890a-c7102d704ef6_1400x1000.jpeg)

Superb as usual. I think I'd consider myself, probably unsurprisingly, a functionalist. More specifically a computationalist. Boring, I know ;)

My question is, isn't the hard problem of consciousness by definition unscientific? And I don't mean it in a pejorative sense. Science, interpreted mostly as falsificationism, is a pretty narrow epistemic system. The hard problem of onsciousness for me seems to be asking precisely the type of questions that science is unequipped to answer: "why".

Well presented, it's a complex topic explained clearly. I hope you'll take this as constructive feedback rather than criticism, but why promote the merits of physicalism as the consensus among neuroscientists? Would you find it strange if someone promoted the merits of a neuroscience theory by mentioning the consensus opinion among philosophers?