Functionalism: The Mind is What the Brain Does.

Consciousness Theories. Physicalism #4

Welcome to Part 4 of our series on physicalism, the theory that the physical world can fully explain consciousness. This week we’re exploring functionalism — currently the most popular theory in the philosophy of mind and in scientific fields that study consciousness — like cognitive neuroscience. But just because a theory is popular doesn’t make it true. So, let’s explore the merits of the functionalist’s claims.

As we have done with other consciousness theories, we’ll ask three questions:

What is functionalism?

Why might someone believe in functionalism? and,

What are the main arguments against functionalism?

Unlike other consciousness theory articles, functionalism will be addressed in two parts. Let’s address the first two questions this week and leave question 3 for next week.

But before we jump into the questions, let’s do a little recap.

Way back in the series on The Five Most Controversial Ideas in the Study of Consciousness, we started with some non-physicalist views. We looked at Descartes' substance dualism and epiphenomenalism. Both of these theories claim that when it comes to consciousness, there are two things: the physical brain and the mind, which is not made of physical things.

In this series on physicalism, we will review some of the main alternatives to these non-physicalist views. So far, we’ve explored one of these theories — the mind-brain identity theory (aka reductive materialism), which is the view that the mind is the brain. In the article on the identity theory, we spent some time discussing what might be meant by the word ‘is’ in their claim that the mind is the brain.

This article is going to draw heavily on what we discussed in the identity theory article, so if you need a recap, here’s the link:

Great! Let’s get into the questions.

Q1: What is Functionalism?

Functionalism emerged as a response to two earlier theories of mind: the identity theory (which we explored in Part 3) and behaviourism (which we haven’t discussed yet). While functionalism incorporates elements from both of these earlier theories, it also significantly departs from them.

There are many different types of functionalism. Not all of them agree with each other. But what is agreed is that when it comes to defining mental states, what matters is the role or job of the mental state, not what it is made of.

Like the identity theory, functionalism is a physicalist theory. But the functionalists think consciousness is a different type of physical kind than the identity theorists claim.

For the identity theory, consciousness is the brain kind. But for functionalists, consciousness is — the functional kind.

So, what is a functional kind?

Some things are defined by what they do — not by what they are made of.

Functional kinds are the kinds of things that are defined by their inputs and outputs. More specifically, the kinds of things where the inputs are causes and the outputs are effects.

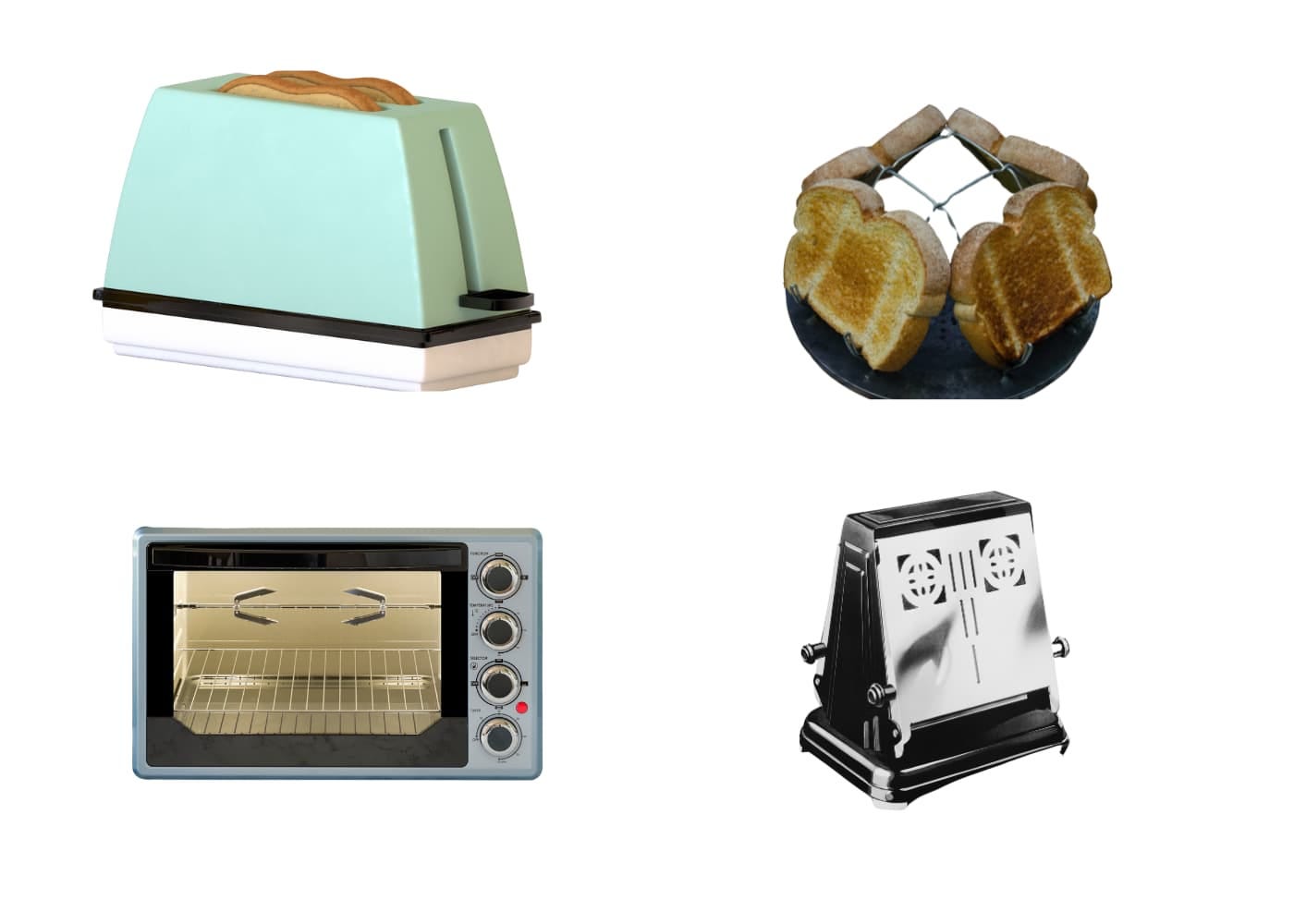

For example, a toaster is a functional kind. The function of a toaster is to toast bread — to input bread and, after a short time, to output toast. The toast is the output effects of the function of the toaster. And we define a toaster by the function it performs. If a toaster does the job of toasting — it’s a toaster. It doesn’t matter what a toaster is made of or what it looks like; as long as it toasts, we define it as a toaster.

Not all things are functional kinds. For example, we probably wouldn't define water solely by its function. We tend to define water by what it is made of (H₂O) or by its physical properties, such as being a clear, odourless, tasteless liquid at room temperature that freezes at 0°C and boils at 100°C at standard atmospheric pressure. While water certainly has many functions (like hydrating living organisms or eroding landscapes), these functions don't define what water is in the same way that toasting defines a toaster.

Poison is another example of a functional kind. The function of poison is to cause harm or death when ingested, inhaled, or absorbed. We define poison by this function, not by its chemical composition or physical properties.

It is true that when we define specific poisons, we define the chemical composition of that specific poisonous substance. But when we define the concept of poison itself, we define it by the function it performs — input a substance and output the harmful effects. This definition of poison holds regardless of the specific chemical makeup of a poison. What matters is the function — if a substance poisons, it's a poison.

We might wonder about other examples we’ve discussed so far. Is a table a functional kind? What about a hat? Or a ship?

If something performs the function of a table — it holds objects at some height above the ground — we call it a table. And if something performs the function of a hat — we can wear it on our head to shield our face from the sun — we call it a hat.

You can probably see where we are going here.

Functionalism claims that mental states are a functional kind. We define consciousness by the functions that are performed — input a cause and output an effect. The definition of a conscious mental state holds regardless of the physical substrates that implement these functions. It doesn't matter what the substrate is made of. As long as it performs the right type of function, it's conscious. Just as a toaster is defined by its function of toasting, regardless of its physical composition, conscious mental states are defined by their functions, regardless of whether they are implemented in biological neurons, silicon chips, or any other medium capable of performing these functions.

Q2: Why might someone believe in Functionalism?

When something can be implemented in many different systems, it is said to be multiply realisable.

Multiply realisability is a key principle in functionalism because functional kinds are multiply realisable.

Tables, toasters, hats, and poison are multiply realisable — they can be made from many different things. As long as they continue to perform the function that defines them, they don’t lose their definition.

This is not true for brains. Brains are defined by what they are made of — by their biological structure. So, when the identity theory claims that the mind is the brain, they are making a claim about what mental states are made of — mental states are brain states. And, according to the identity theory, because mental states are brain states, mental states must be made out of brain stuff — they are not multiply realisable.

This brings us to the key question that defines the debate between the identity theorists and the functionalists:

Are mental states multiply realisable?

If mental states are only implemented in one type of system, we might suggest that the evidence favours the identity theory. But, if mental states can be implemented in many different systems, the functionalists might have the stronger claim.

Let’s review the evidence:

Brains are diverse

Learning requires the strengthening and weakening of neural connections. Your brain would have formed connections when you learned language as a child. But the connections that formed in your brain will almost certainly be different from the connections formed in mine. Even if we both learned the same language.

Imagine Sally and Jose. Sally and Jose both learned English as a child. Because brains develop differently, they do not have the same wiring. But here’s the thing — it doesn’t matter. Sally and Jose can both understand and speak English. It doesn’t matter which neurons fire; it's about getting the job done. And despite how diverse their brains are — they still achieve the same results — they understand and speak the same language.

Brains Across Species

Last week we discussed the octopus. These creatures are very different from humans, with a common ancestor roughly 550 million years ago. Octopus brains are very different from ours — most of their neurons aren't even in their central brain but in their arms!

Yet, despite these differences, octopuses display some remarkably similar functions to humans. They can solve complex problems, use tools, and even show signs of play behaviour. They're capable of learning, remembering, and adapting to new situations — much like we do.

It doesn't matter that an octopus brain is wildly different from a human brain. What matters is that both can perform similar functions — both can learn, problem-solve, and adapt. The physical stuff doesn’t matter — it’s about getting the job done.

Brains Change

Our brains have an incredible capacity to adapt and reorganise themselves, a property known as neuroplasticity. Studies of blind individuals, particularly those who lost their sight at a young age, provide a fascinating example of this.

In people with normal vision, the visual cortex primarily processes visual information from the eyes. However, in individuals who are blind, particularly those who have been blind since early childhood, the visual cortex doesn’t sit idly. Instead, it adapts to serve other functions. It gets repurposed for other sensory processing. For instance, when blind individuals read Braille, their visual cortex is often highly active — it’s not processing visual information — it’s processing tactile information from the fingertips.

Studies have shown that blind people often have enhanced auditory abilities, and their visual cortex shows increased activity when listening to sounds or speech. The brain has essentially rewired itself, using the available neural real estate to enhance other senses.

This adaptability isn't about preserving specific brain structures or connections. What matters is that the brain finds a way to perform necessary functions, even if it means completely repurposing areas typically used for something else. To perform the function of reading braille, it doesn't matter whether it's the visual cortex doing the work or some other part of the brain; what matters is that the reader can effectively get information from and interact with their environment. It's not about which specific neurons are doing the job but about getting the job done.

Brains can deal with Artificial Aids

Our brains have a remarkable ability to adapt to and integrate artificial inputs as long as they serve the same function as natural ones. A prime example is the cochlear implant — a device that has revolutionised the treatment of severe hearing loss.

Cochlear implants don't work like normal hearing. They bypass damaged parts of the ear and directly stimulate the auditory nerve with electrical signals. These signals are very different from what the brain normally receives from a functioning ear. Yet, with time and practice, the brain learns to interpret these artificial signals as sound.

What's fascinating is that it doesn't matter to the brain that the input comes from an electronic device rather than natural hair cells in the cochlea. The brain adapts to process this new input type, ultimately achieving the same function: hearing. People with cochlear implants can understand speech, enjoy music, and perceive environmental sounds, even though the signals their brains are receiving are fundamentally different from those in natural hearing.

This adaptability extends to other sensory substitution devices as well. For instance, some devices convert visual information into tactile sensations, allowing blind individuals to "see" with their skin. Again, the brain adapts to interpret these unusual inputs meaningfully.

The Sum Up (so far)

The evidence from diverse brain structures, cross-species comparisons, neuroplasticity, and adaptation to artificial aids suggests that mental states are multiply realisable — at least in brains. The examples above suggest that what matters is the function being performed, not the specific neural structure.

BUT! Let’s not jump on the functionalist bandwagon before considering the arguments against functionalism. We'll explore these arguments in detail next week.

For those interested in doing more in-depth reading on functionalism, these are the main resources I used for this article (if you are new to functionalism, I recommend the article by Adam Bradley):

The Nature of Mental States, by Hilary Putnam

Troubles with Functionalism, by Ned Block

The Causal Theory of the Mind, by D.M. Armstrong

Mind, Language, and Reality, by Hilary Putnam

A Primer on Multiple Realizability and Functionalism, by Adam Bradley

Thank you.

I want to take a small moment to thank the lovely folks who have reached out to say hello and joined the conversation here on Substack.

If you'd like to do that, too, you can leave a comment, email me, or send me a direct message. I’d love to hear from you. If reaching out is not your thing, I completely understand. Of course, liking the article and subscribing to the newsletter also help the newsletter grow.

If you would like to support my work in more tangible ways, you do that in two ways:

You can become a paid subscriber

or you can support my coffee addiction through the “buy me a coffee” platform.

I want to personally thank those of you who have decided to financially support my work. Your support means the world to me. It's supporters like you who make my work possible. So thank you.

I guess my problem with functionalism boils down to not liking black boxes. It matters to me *how* a function is accomplished, and that seems to make the *what* (it is) important. Going back to the laser light analogy, many diverse physical systems can produce laser light, but they all share important common properties. So, I would expect that consciousness being (potentially!) realized in multiple ways still implies constraints on how and what.

In particular, I resist the notion often expressed by functionalists that a software simulation of a physical process has a real identity with that physical process.

Now, on to part two! 😃

Love this! Functionalism feels like "the purpose of a system is what it does" heuristic applied to the brain. Super interesting stuff as always Suzi, you've given me a lot to think about :)