I recently learned about Charles — and I immediately liked him very much.

In the 1950s, at the Naples Zoological Station, there lived three octopuses named Albert, Bertram, and Charles.

Peter Dews, a Harvard scientist, was attempting to train Albert, Bertram, and Charles to pull a lever that would turn on a light and deliver a piece of fish.

Albert and Bertram had no problem learning how to pull the lever. In his notes, Dews wrote, "Albert and Bertram gently operated the lever while free-floating."

Charles, on the other hand, was not so accommodating.

“Charles anchored several tentacles on the side of the tank and others around the lever and applied great force. The lever was bent a number of times, and on the 11th day was broken, leading to a premature termination of the experiment.”

Albert and Bertram were not interested in the light. But Charles... Well, Charles seemed either fascinated by or completely annoyed by it.

Dews wrote:

Charles repeatedly encircled the lamp with tentacles and applied considerable force, tending to carry the light into the tank. This behavior is obviously incompatible with lever-pulling behavior.

But, it seems Charles did not only have an issue with the light. Charles also took issue with Dews.

Dews continues:

Charles had a high tendency to direct jets of water out of the tank; specifically, they were in the direction of the experimenter. The animal spent much time with eyes above the surface of the water, directing a jet of water at any individual who approached the tank. This behavior interfered materially with the smooth conduct of the experiments, and is, again, clearly incompatible with lever-pulling.

This week we are exploring the mind of the octopus. We’re asking two main questions:

How intelligent are octopuses? and

What does the octopus brain tell us about what a brain can be?

Note: Many of the examples I use in this article I first learned from reading Peter Godfrey-Smith’s book, Other Minds. This is a fascinating read. I highly recommend it to those who want to learn more about animal intelligence and consciousness.

And for those who like documentaries, National Geographic has just released a new series called Secrets of the Octopus, which is simply amazing viewing.

But first, an important caveat:

Some have argued (or maybe just wondered) whether our Recalcitrant Octopus, Charles, could not learn the lever-pulling task because Charles simply lacked the cognitive ability to do so. This is a possibility. And, as with all animal research (and AI research, too), we need to be careful not to anthropomorphise animals (and AI) — assuming they have internal motives and abilities they simply do not have. This is a legitimate concern. But we must also be careful not to be too anthropocentric — assuming humans are the most significant and important beings.

So we might want to ask, was Charles unable to learn the lever pulling task? Perhaps. But it is also possible that Charles simply found lever-pulling uninteresting compared with pulling the lamp into his tank and squirting the experimenter.

Q1: How Intelligent are Octopuses?

Octopuses seem to be seriously clever.

Measuring intelligence is tricky though (possibly because it is a difficult thing to define). But scientists have some clever ways to get a sense of how smart different animals might be. Let’s take a look at five of these indicators and how they relate to octopuses.

1. Tool Use

Tool use is often considered an indicator of intelligence. If an animal can use tools, it suggests that the animal is able to learn and adapt. Tool use is a rare skill that is often associated with stereotypically smart animals like apes, monkeys, dolphins and some birds.

Octopuses use tools. In fact, octopuses use tools in a very interesting way. Most tool use in the wild is seen when an animal uses a tool to solve a current problem. For example, orangutans have been seen using leaves as umbrellas when it rains. Octopuses, however, have been seen carrying tools with them for later use.

For example, octopuses have been seen carrying half a coconut shell that could be used as protection at a later time. Sometimes, they have been seen carrying two coconut or clam shells to construct a ball-like shelter that they assemble and disassemble as needed. As you might imagine, carrying coconut shells isn't easy for an octopus, and doing so makes the octopus more vulnerable to attack from predators. But they seem to be willing to accept this short-term risk to avoid a longer-term vulnerability.

Carrying tools for later use is a skill only witnessed in humans, chimpanzees, crows, and octopuses.

Below is a short clip of some footage of an octopus carrying a coconut shell:

2. Individual Recognition

The ability to recognise or identify others can be an important skill for an animal to have. This is especially true for animals that rely on social interactions, monogamous mating, and parent-offspring recognition.

The interesting thing about octopuses is that they are not known for being social or monogamous, and once their young hatch, they don’t care for their young (the female octopus usually dies after their baby octopuses hatch).

But an octopus can recognise individuals. And not just individuals within its own species — they can also distinguish between humans.

Much evidence shows that octopuses will recognise and behave differently toward different researchers. In one lab in New Zealand, an octopus seemed to dislike one researcher. Every time this researcher passed the tank, she was squirted in the back of the neck. This was true even when all the researchers wore identical lab coats.

3. Problem Solving

There is plenty of evidence that octopuses can navigate mazes, solve puzzles and figure out how to open and close containers. But some of the most entertaining stories about octopuses involve anecdotal accounts of octopuses' mischievous behaviour of escaping and stealing.

One such tale recounts an incident in a laboratory where fish mysteriously disappeared from their tank. To find out what was going on, the scientists set up a video camera to catch the culprit. The octopus stealthily escaped its own tank, raided the fish tank, devoured its catch, and meticulously covered its tracks before returning to its own enclosure.

Peter Godfrey-Smith recounts some fascinating encounters between researchers and octopuses in his book Other Minds. In many of these encounters, the octopus’s behaviour seemed to be aimed at manipulating their environment. One such case involved octopuses learning to extinguish lights by strategically squirting water at the bulbs. Octopuses don’t like bright lights, and squirting water jets managed to short-circuit the power supply. At the University of Otago in New Zealand, this behaviour became so frequent and costly that the researchers ultimately decided to release the octopuses back into their natural habitats.

While this behaviour might appear to be a form of problem-solving, some have argued that it is unclear whether the octopuses truly understood the connection between their water-squirting actions and the resulting darkness. Although it is well-established that octopuses dislike bright lights and tend to squirt water at things they find unpleasant, the extent to which they grasped the cause-and-effect relationship remains uncertain. However, the evidence suggests that these creatures learned this behaviour quickly and tended to only squirt the lights when researchers were not present.

4. Understanding other Minds

This leads us to the idea that octopuses might be able to understand the minds of others. I mention this one hesitantly because such strong claims require strong evidence. But the evidence is mounting that octopuses seem to watch others and adjust their behaviours according to who is watching.

In the wild, octopuses are known for their shapeshifting abilities. They will change shape and colour to blend in or stand out. Depending on which others are around, octopuses can change their bodies' colour, shape, and texture to hide or exploit the fears of other creatures. For example, when faced with a predatory shark, an octopus might change its colour to match the surrounding coral and remain undetected. On the other hand, when threatened by a damselfish, an octopus might spread its arms and change its colour to a striking black-and-white pattern to mimic the appearance of a venomous sea snake.

In the laboratory, octopuses are known for their Houdini-esque escape artistry. Indeed, keeping octopuses requires serious measures to ensure they don’t flee. But they always seem to try their escape when no one is watching. As one experimenter at the National Aquarium of New Zealand explained, an octopus will seem content floating in their tank until your attention is distracted, and then the octopus will make its escape.

In another example of octopuses seeming to understand the minds of others, an experimenter was feeding her octopuses some thawed squid. It’s important to note that octopuses do not particularly like thawed squid. After she had fed all the octopuses, she walked back to the first tank. The octopus in that tank had been watching and seemingly waiting for her to return. This octopus had not eaten the thawed squid but was holding it with one of its hands. When the experimenter reached the tank, the octopus moved towards the outflow pipe of its tank. While watching the experimenter, the octopus dumped the thawed squid down the pipe.

Perhaps the most striking example of an octopus seemingly understanding the minds of others comes from the new National Geographic documentary series Secrets of the Octopus. While diving off the coast of Australia, Dr Alex Schnell meets an octopus and uses pointing gestures to indicate the location of hidden crabs. Astonishingly, the octopus seems to understand, moving towards and exploring the indicated locations. At first thought, understanding pointing gestures might seem like a simple thing, but comprehending pointing is a complex cognitive ability. It requires an understanding of the intention behind the gesture. The pointer is not simply making a shape with their hand but wants the viewer to follow the direction of the extended finger to a location in the environment. Human children don't tend to understand pointing until 9 to 12 months of age.

5. Brain Size

As a rough indicator, scientists often use the size of an animal's brain relative to its body to calculate estimated cognitive capabilities. It’s not an exact science — there are many examples where the correlation of brain size to cognitive abilities doesn’t fit well, but relative brain size gives us some indication as to how much a species is investing in its brain. The octopus has a brain-to-body ratio that surpasses most invertebrates (e.g. insects, crustaceans, and spiders) and even rivals some vertebrates.

Q2: The Octopus Brain

The octopus brain is very unlike most vertebrate brains. In fact, it appears that octopuses don’t just have one brain — they have nine! About one-third of an octopus’s neurons are centralised and found in its head. But the other two-thirds are found in its arms. Each arm of an octopus has a bundle of neurons (called ganglia) that can function like an individual brain.

This means that each arm of an octopus can perform complex tasks and react to the world without direct input from the central brain or the other arm's brains.’ Each arm's brain controls its arm's movements and senses of touch, smell, taste, and maybe even light.

As we can see, the separation between brain and body is less defined in an octopus than in a human.

Humans have a centralised brain that coordinates bodily functions. This means we often think of the brain and the body separately — the brain controls the body, and the body sends information to the brain.

Octopuses, on the other hand, have a distributed neural system. With each arm possessing its own mini-brain capable of independent decision-making and sensory perception, the lines are blurred between where the brain ends and the body begins.

This makes us wonder. What would it be like to be an octopus? What would it be like to experience the world through multiple semi-autonomous brains?

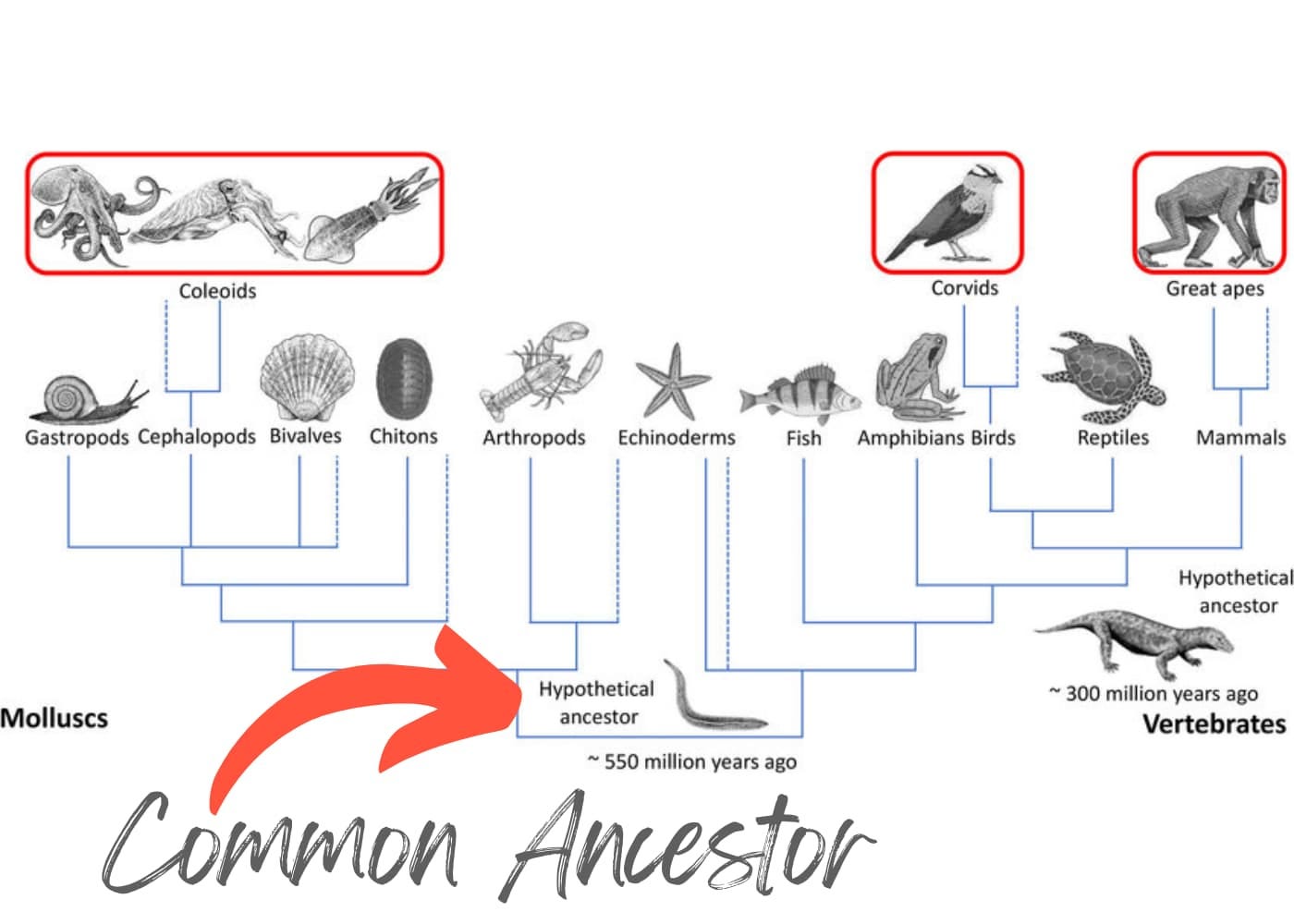

Despite their intelligence, octopuses are not closely related to humans on the evolutionary tree. The common ancestor of octopuses and humans was considered a primitive creature that likely lacked the sophisticated traits we typically see in octopuses and humans.

What is remarkable is that despite this distance on the evolutionary tree, octopuses and humans have evolved to have similar complex traits. Both humans and octopuses have eyes that act like cameras, with lenses that focus images on our retinas. Both seem to have the capacity for learning through reward and punishment, short-term and long-term memory, tool use, REM sleep (and likely dreaming), problem-solving abilities, individual recognition, and possibly the ability to understand the minds of others.

There is no evidence that our shared ancestor possessed any of these complex traits. If we take the above evidence as true, it means that complex camera eyes, the ability to learn from rewards and punishments, short-term and long-term memory, tool use, REM sleep, dreaming, problem-solving, individual recognition, and the ability to understand other’s minds evolved more than once. Octopus and human intelligence seem to have evolved independently.

And on the question of consciousness…

If octopuses are conscious, then we might start to wonder…

Did consciousness evolve more than once? What evolutionary advantage does consciousness have? Is consciousness an essential feature of complex life (or all life) rather than a unique development in Earth's history? And what does this mean for consciousness in other animals?

If you are interested in reading more about animal consciousness, you might be interested in reading the following articles:

Thank you.

I want to take a small moment to thank the lovely folks who have reached out to say hello and joined the conversation here on Substack.

If you'd like to do that, too, you can leave a comment, email me, or send me a direct message. I’d love to hear from you. If reaching out is not your thing, I completely understand. Of course, liking the article and subscribing to the newsletter also help the newsletter grow.

If you would like to support my work in more tangible ways, you do that in two ways:

You can become a paid subscriber

or you can support my coffee addiction through the “buy me a coffee” platform.

I want to personally thank those of you who have decided to financially support my work. Your support means the world to me. It's supporters like you who make my work possible. So thank you.

Wonderful analysis. It is amazing to find out the level of cognitive abilities for all creatures.

Charles is a hero. It reminds me of the horse in Kate Crawford’s book The Atlas of AI. Rightly or not, I assume all living things have intelligent—it’s just a matter of levels in the spectrum. I love hearing another proof of this. Consciousness? Your writing and other investigations seem to be pointing towards a similar multi dimensional spectrum. But to attribute ‘consciousness’ to animals could be a reduction of the concept since we don’t completely grasp the extent of the concept of consciousness in humans. To make the attribution presupposes humans are just (advanced) animals—which may or may not be true. Evidence suggests humans are more amazing and more destructive than any other animals. So there is something clearly different—good and/or bad about human creatures. Octopi aren’t making air bubbles and terrariums for humans to study them in underwater laboratories—though give Charles descendants a chance and they just might get there someday.