Welcome to Part 2 of our series on physicalism, the theory that the physical world can fully explain consciousness.

This article will draw on concepts we covered in Part 1. So, if you haven’t done so already, you may want to read Part 1 before reading this article, especially if you are new to physicalism theories.

Part 1:

Most evenings, my husband, Pete, and I take a walk to catch up on each other’s day. During these walks, Pete often asks me what I’m currently writing about. When I mentioned this article, he laughed and said, “Okay, so you’re going to try to cover the entire field of metaphysics in 2,000 words!”

He might have had a point.

This is a huge topic. Answering the question of what exists might be an impossible task—even with all the words in the world.

But setting a framework for understanding what types of things might exist in our world and how we might differentiate between them is essential for understanding consciousness and will be especially important for understanding why proponents of each physicalist theory adopt the stances they do.

So, this week, let’s take some tiny steps towards trying to answer the question — what exists?

We’ll do this in 3 steps:

First, we will outline a framework to think about what exists,

Then, we will see how our physicalist theories fit within this framework,

And finally, we will review a radically different way of thinking about what exists.

But first, two quick caveats:

One

This article will borrow heavily from the work of theoretical physicist Sean Carroll. When planning this article, I was wary of committing to any particular framework, as I was concerned that doing so might inadvertently imply an acceptance of the assumptions inherent to the chosen framework.

Understandably, traditional frameworks from philosophers like Aristotle and Plato do not incorporate new scientific understandings from modern physics. Carroll provides a modern physicalist framework that accounts for these scientific developments, making it a good place to start our discussion on physicalism.

Two

Given that emergence will be a key concept in this article, we should try to define it. Emergence refers to the observation that the whole is, or at least seems, greater than the sum of the parts. For example, we know that a table is made of atoms. We are told that atoms are mostly empty space. But somehow, solid tables emerge from the complex way atoms and forces interplay.

Emergence is one of those words that is often used without being clearly defined. It can be used in the weak sense, which means the emergent phenomena could be, at least in principle, explained by its parts. With weak emergence, the emergent property is said to be reducible to its parts. Strong emergence, in contrast, means that the emergent phenomenon is something entirely new that cannot be explained or reduced to its parts.

So what do you think? Do tables emerge from atoms and forces in the weak sense — could we, in principle, explain tables with their fundamental parts? or do tables have properties that cannot be explained or reduced to their parts?

The critical question is….

Are emergent phenomena just a different way of talking about the same thing, or are emergent phenomena something completely new? In other words, are emergent phenomena real or simply illusions that seem real?

1. A Framework to Think About What Exists

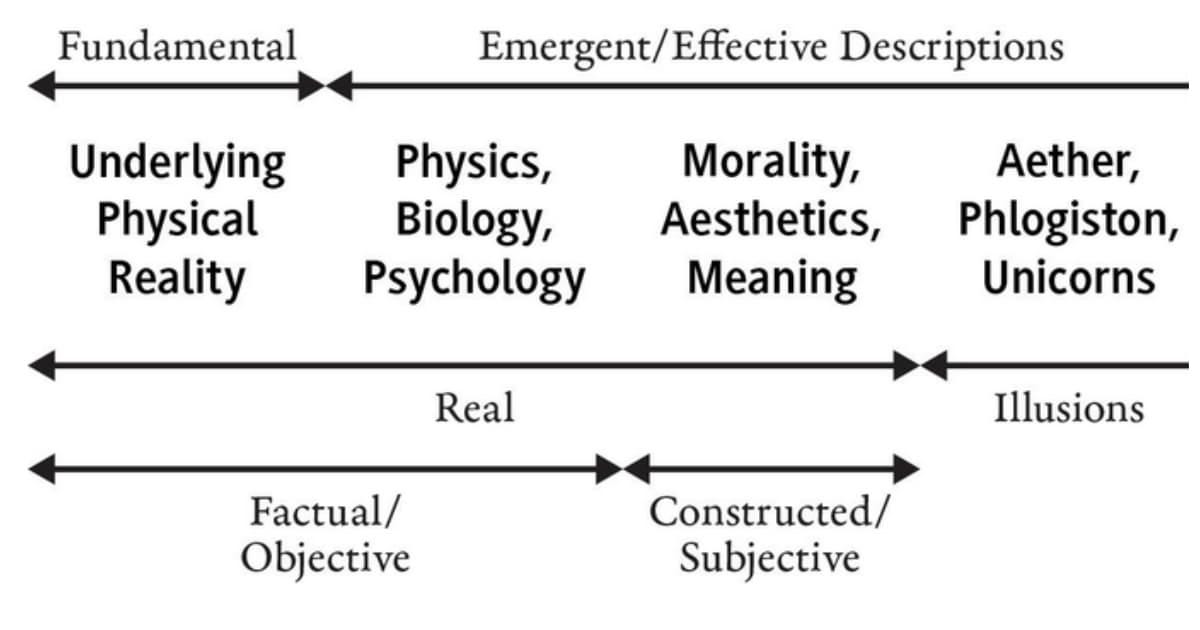

The figure above is from Carroll’s book The Big Picture. The idea behind this image is to distinguish between different levels of reality. There’s a lot going on in this diagram, so let’s break it down.

1. Fundamental level

On the far left of the diagram, is the fundamental, real and objective level. This category refers to the most basic particles, fields, and first principles from which the physical universe seems to be constructed, according to our best scientific understanding. They represent the foundational concrete bits and pieces of reality itself. Examples could include subatomic particles like quarks and leptons, fundamental forces like gravity and electromagnetism, or the most elementary units of space and time.

2. Macro level

The second category, which I call the macro level, includes emergent, real, and objective things. These are the larger-scale objects, entities, and structures we directly experience and interact with daily. Examples include human bodies, animals, planets, stars, tables, and chairs. Interestingly, Carroll includes psychology in this category, which, no doubt, some readers will quibble over.

3. Constructed level

The constructed level includes emergent, real, and constructed things, such as concepts, ideas, and constructs. These things don't have a concrete physical form, yet we treat them as real and critically important aspects of our existence and experience. Carroll includes morality, aesthetics, and meaning in this category. Social constructs like money, marriage, and shared cultural or linguistic frameworks will also be included here.

4. Illusions

Illusions are the concepts, ideas, and constructs that don't correspond to any concrete physical reality but are rather imaginative fictions, hypothetical notions, or products of incorrect beliefs and reasoning. Examples might include movie characters, mythical creatures like unicorns, illusory percepts like visual illusions, or incoherent abstractions like the idea of a married bachelor or a square circle.

After laying out this framework, I would be surprised if you did not question some of the distinctions and assertions made here. For example, we might question whether morality is really subjective or whether something imagined might someday be real.

These are great questions to ask, but in this article, I want to focus on one claim in particular — the claim that so many things should be considered real.

Should we consider emergent things as real things?

Let’s explore an example.

Do ships exist?

If I took my four-year-old nephew to Sydney Harbour and asked him — what is a ship? He would have no problem pointing out several large sea vessels transporting people or goods. He would also have no problem informing me that a small tugboat was not a ship.

If I asked my physicist friend the same question, she might cheekily answer that a ship is simply an arrangement of atoms.

It seems that when we are talking about ships we can talk about them in different ways. Sure, my physicist friend would be correct; at the fundamental level, ships are simply made of protons, neutrons, and electrons. But so, too, is every other physical thing in our universe.

Perhaps ships are best thought of at the macro level — in terms of their shape and size — or maybe the constructed level is more fitting because we define ships as the concept of large sea vessels carrying things.

Defining a ship can be tricky. We often resort to definitions like — a vessel that floats and is larger than 60 meters long. But such definitions are arbitrary. Why 60 meters? Why should a sea vessel that is 59.99 meters long lose its shipiness?

2. How do the Physicalist Theories Fit Within the Framework?

Let’s tie the above framework with the four physicalist views. As a reminder, here’s a super quick review of the four physicalist views we defined in Part 1:

Identity Theory (aka Reductive Materialism)

Conscious states are identical to brain states.

Functionalism

Consciousness is what the brain does, not what it is made of.

Eliminative materialism

Conscious states, like thoughts, feelings, perceptions, intentions, experiences, beliefs, and desires—don't actually exist.

Non-reductive materialism

Consciousness cannot be completely reduced to physical properties.

Below are four key questions (based on those raised by Carroll in The Big Picture). How we answer these four questions will seriously affect how we think about consciousness and reality. Most of the disagreements between the different physicalist views will be based on disagreements about how we should answer the following four questions.

Question 1: Is the fundamental level the really real level?

Science has developed an intense fascination with probing the fundamental, microscopic levels of existence.

There is often an underlying assumption that goes along with this fascination — the basic building blocks of matter and energy are what reality really is. All other emergent levels are sort of real. Tables are real, but not really real.

If emergent things are not really real, are they part real but also part illusion?

When we talk about consciousness, at what level of reality are we talking? If we think consciousness best fits the fundamental level — does that mean we accept some form of panpsychism? And if we think consciousness best fits an emergent level — does that mean we accept that consciousness is part illusion?

Perhaps the fundamental level isn’t the only real level. Other levels of reality might be just as real. This is the position Sean Carroll takes.

Question 2: To understand something at an emergent level, do we first need to understand the lower levels?

To understand the brain, do we first need to understand quantum mechanics and particle physics? The answer to this question might seem to be an obvious no. Again, Sean Carroll would suggest that it seems obvious that neuroscientists can happily learn about how the brain works without needing to understand the intricacies of quantum field theory and the standard model of particle physics.

However, not all would agree with this seemingly obvious answer. Proponents of strong reductionism would argue that emergent phenomena can only be really understood when explained at the fundamental level. To truly understand something means we have explained it according to the fundamental level.

A reductive materialist might hold that neuroscientists could progress towards understanding how the brain works by studying processes like attention, perception and consciousness, but they would consider such understanding limited and potentially incorrect until it is grounded in a lower-level explanation.

Question 3: Can we learn about something at an emergent level that we can’t learn from the fundamental level? Even if we knew everything there was to know?

If we could understand everything — absolutely everything — at the fundamental level, would we really know everything there is to know about what exists?

If we want to know how the brain works, would understanding all the atoms, particles, forces, molecules, and their relative positions really explain how we remember our first kiss, how the ocean smells after a storm, or the lyrics to our favourite song? It seems that we really do learn something new from the emergent level.

To many, the idea of reducing complex phenomena entirely to the fundamental level is misguided. Projects like the Human Genome Project provide a cautionary tale against making such claims. Initially, scientists made grand promises that mapping the complete human genome would unlock all the secrets of human biology and allow us to explain and treat all diseases and traits.

But the reality wasn’t so grand.

Don’t get me wrong. Sequencing the genome was an incredible scientific achievement that has significantly influenced the field's progress. However, it has become clear that simply knowing the genome sequence is insufficient to fully explain human physiology, behaviour, and the nuances of health and disease. The genome alone does not hold all the answers we hoped it would.

But someone might argue — if we know the genome sequence, do we really know everything there is to know? Perhaps not. Perhaps while our current understanding at the lower level is limited, we rely on higher-level theories to understand our world.

An eliminative materialist might argue that we will rely less on our higher-level theories of consciousness as we discover more about the lower levels. With new knowledge, we might come to understand that we were confused about our higher-level theories. We were incorrect. The phenomena we thought existed don’t actually exist and can be eliminated.

Question 4: Can a theory at an emergent level be incompatible with — literally inconsistent with — a theory at the fundamental level?

Now we are stepping into much more controversial territory. If we answer yes to this question, we are advocating for a type of strong emergence. That is, we believe that the emergent level explains something totally new. Even if we know everything there is to know about the fundamental level, we will never be able to predict or explain the emergent level. The behaviour at the emergent level is not reducible to the sum of its parts.

This is the claim of the non-reductive materialist. The non-reductive materialist agrees that a whole at an emergent level (e.g. a person) is made of fundamental parts like atoms. But they also make a stronger claim. They argue that the person level affects the atoms, which cannot be explained by all the other atoms and forces that make up the person. There is an effect of the whole on the individual parts.

3. A radically different way to think about what exists.

We’ve seen how reductive, non-reductive, and eliminative materialism might answer these sorts of questions, but functionalism has been a bit quiet on this topic.

Although there are many different versions of functionalism, some functionalist views reject Sean Carroll’s idea of levels of reality, claiming that given our understanding of fundamental physics, this idea doesn’t make much sense. I’m referring here to a branch of functionalism called functional reductionism.

Traditionally, functionalism is a theory about consciousness — it claims that conscious states are functional states — a conscious state is as a conscious state does. But functional reductionism makes a stronger claim, suggesting that it is not just conscious states that are functional states. Proponents argue that everything that exists, from subatomic particles to consciousness, can be fully explained and defined by functions and processes with no remainder. It is ‘functions all the way down.’

Functional reductionism has become increasingly popular in the sciences, particularly in physics, perhaps because of its compatibility with fundamental physical theories like quantum mechanics. For example, Knox (2019) and Lam and Wüthrich (2018) suggest that instead of defining spacetime in terms of a 4-dimensional geometry, spacetime should be explained in terms of its functional role — spacetime is as spacetime does.

This represents a radical departure from our everyday conception of reality. We’ll return to this idea briefly when we discuss functionalism.

But next, in this series on physicalism, we will explore The Identity Theory — the idea that conscious states are identical to brain states.

Thanks so much for reading this article.

I want to take a small moment to thank the lovely folks who have reached out to say hello and joined the conversation here on Substack.

If you'd like to do that, too, you can leave a comment, email me, or send me a direct message. I’d love to hear from you. If reaching out is not your thing, I completely understand. Of course, liking the article and subscribing to the newsletter also help the newsletter grow.

If you would like to support my work in more tangible ways, you do that in two ways:

You can become a paid subscriber

or you can support my coffee addiction through the “buy me a coffee” platform.

I want to personally thank those of you who have decided to financially support my work. Your support means the world to me. It's supporters like you who make my work possible. So thank you.

Good article!

I differentiate materialism from physicalism based on, respectively, weak versus strong emergence (and align with the latter). I think there are emergent properties that are real and cannot be explained by their low-level properties. (As one of the most complicated and amazing emergent properties, I think consciousness easily fits in the category.) Per your questions: No (just the fundamental level); Not always, but with the brain, maybe; Yes, absolutely; No to "inconsistent", but yes to "totally new" (higher properties must be consistent with lower ones but can be unexpected).

That framework reminds me vaguely of Plato's divided line. Your "macro level" corresponds with the classical physics level. That division between the fundamental quantum world and the emergent classical one being one of the greatest mysteries in science. Besides consciousness perhaps one of the most urgent places the question of strong emergence arises.

If unicorns aren't real, how is it we all know exactly what the word refers to? If money and marriage are constructs, aren't unicorns as well? 🦄😊

My question when it comes to functionalism is what implements the function? What does the doing? It doesn't seem helpful to view spacetime that way. I take functionalism to be about equivalence between, for instance, our brains and something that replicates their function. A functionalist approach to spacetime suggests to me the notion of something else replicating that functionality.

Looking forward to reading more!

(I hope you'll forgive this: Quarks *are* leptons. One might say "quarks and electrons" to stay in the realm of matter, or "quarks and photons" to cover both particle bases.)

I grasp intuitively the inclusion of constructed subjectivity in the realm of real… Can’t recall the author of the three-world theory (Habermas? Kuhn?), the world, my world, and our world. We behave as if a stop sign is an invisible log in the road. So the stop sign is physical with a constructed function. Because we are conscious (the function of the brain) the stop sign is real to us but not to a dog. Reality is physical; consciousness by modus ponens must also be physical in order to be real (not an illusion). I am incapable at this moment of connecting any of this to your wildly interesting and structured framework. Help me get a foothold here.