Memory Is Your Brain Making Things Up

Why Memory is Not Like Computer Files

Can you remember every word of your favourite teenage movie? Or the words to your favourite song? What about what you wore last Tuesday?

What happens in your brain when you learn and remember?

Last week, we asked if Mary, the brilliant scientist trapped in her black-and-white room, could ever know what red looks like simply by studying facts about colour. The intuition most of us have is — no. There’s something different between learning facts from a book (or television) and learning from experience.

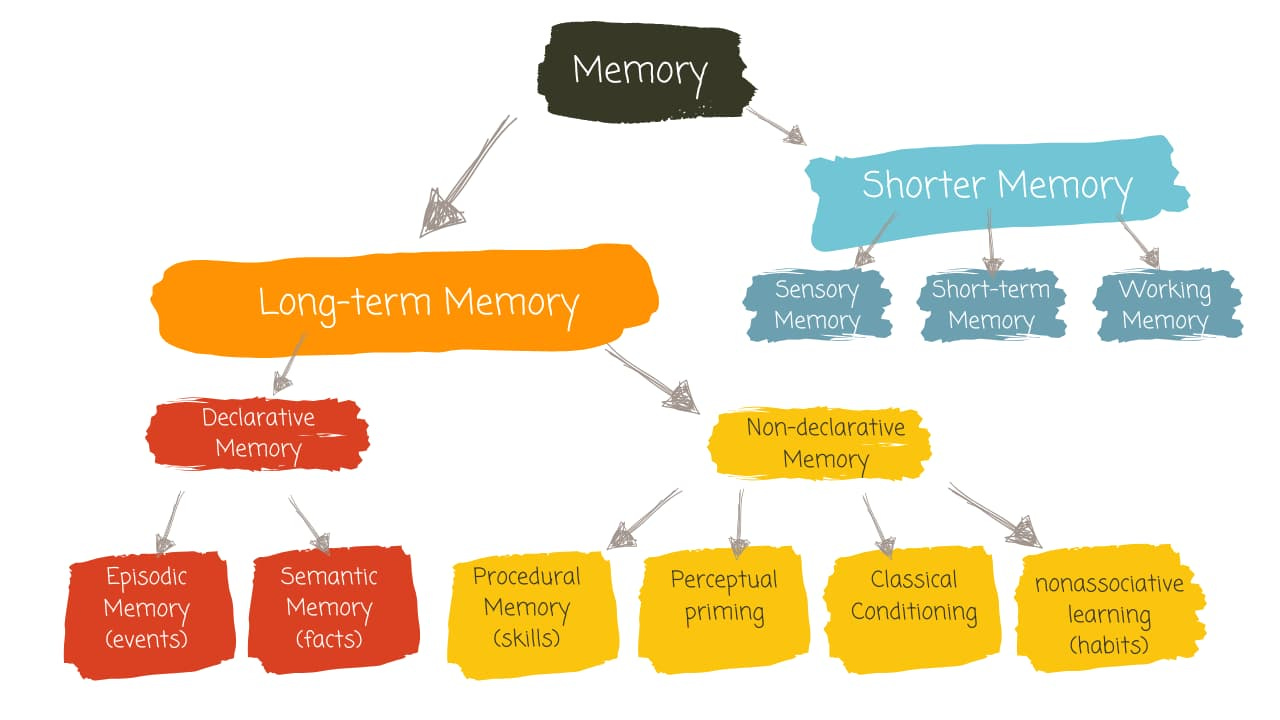

Just as with consciousness — where the word is used to mean many different things — memory is used to mean many things, too. Our brains have multiple memory systems that handle different kinds of knowledge and experience.

Most of the time, these systems work together, but sometimes, they don’t. Understanding how memory works can help us understand how we learn, how we change, and possibly even how to control what we remember and what we forget.

So, this week, we’re asking: how does memory work?

Reviewing the basics of memory this week has an additional advantage. In next week’s article, I want to explore whether we can selectively erase or add memories — like in the movie Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. But before considering whether we can (or should) erase or add memories, we need to understand how memories work normally.

To find out, let’s ask three questions:

What is memory?

How do we get memories into the brain? and,

How do we get them out?

Q1: What is Memory?

When we think about our memory, we might imagine it like facts filed away in our brain for safekeeping — like storing away that Paris is the capital of France or that a platypus glows blue-green under UV light. When we want to retrieve the fact file, it’s tempting to think that we simply scan through our minds and find the memory we want. And even though it is sometimes difficult to find the specific file we are looking for, the file we put in — is in there… somewhere.

But this is not how memory works.

Memory is more of a creative process.

When you remember something, your brain doesn’t simply read out stored information like a computer accessing a file. Instead, it assembles bits and pieces of experience into what feels like a recreation of the original event.

Some fascinating early evidence for memory as a reconstructive process comes from neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield’s work from the 1940s and 50s1.

While performing brain surgery on epilepsy patients (who remained conscious under local anesthesia), Penfield found that when he electrically stimulated certain brain areas, patients would report vivid experiences — kind of like an awake dream. One patient heard an orchestra playing. Another saw a man walking a dog. Stimulating the same spot would reliably trigger a similar experience.

This led some to think memories were stored in specific brain locations, like files in a filing cabinet. But we now know that’s not quite right — the areas Penfield stimulated weren’t storing the memories themselves. Instead, the stimulation was activating distributed networks across the brain, like pressing play to start an orchestra rather than opening a specific file drawer.

Scientists have developed a neat technique called optogenetics that lets them watch and control specific brain cells. Using this tool, they’ve discovered something neat: the same brain cells that fire when we learn something also fire when we remember it. But memories aren’t stored in just one spot in the brain. Think about remembering your last birthday party — you might see the cake, smell the frosting, hear people laughing, and feel the excitement all over again. Each of these aspects of your memory activates different parts of your brain.

The visual cortex is involved, of course, but it doesn’t work alone. Other brain regions jump into action, too — areas involved in processing sound, emotion, context, and objects all contribute to reconstructing the memory. While the reactivation pattern is similar each time we retrieve a memory, it’s never exactly the same. Every time we retrieve it, it changes a little bit.

While scientists have made remarkable progress in understanding how memory works, we are still far from completely understanding what happens when we remember.

But we do know that…

Memory comes in many flavours.

While all our memories involve some kind of reconstruction, how our brain handles different types of information — facts, events, skills — can be quite different.

Let’s look at some of the different ways our brain remembers.

We have the type of memory that Mary would have gained from reading books and listening to television. For example, she would have learned and remembered that the image that hits the retina is actually upside-down. These sorts of memories are facts about the world. We call them semantic memory.

And there are memories about experiences — like the smell of your grandmother’s kitchen, your first kiss, or what Mary would remember about leaving her black and white room. These memories are about events or episodes of our lives — aptly named episodic memories.

Semantic and episodic memories are the type of memories we can declare. They are conscious memories. So, we call them declarative memory.

But we remember unconsciously, too — like remembering how to ride a bike. These are the kinds of memories that are difficult to learn, but we can now remember them without much thought. Remembering how to ride a bike is a type of non-declarative memory called procedural memory.

But even this is just scratching the surface. These are all examples of long-term memories — information we hold onto for years.

We remember in shorter time frames, too. We hold onto fleeting sensory impressions (sensory memory).

Remember the last time your partner asked, ‘Are you listening?’

Let’s be honest: you probably weren’t listening.

But if you were quick enough, you might have been able to grasp what felt like an echo of what your partner said — that’s because you have sensory memory. You grabbed it and avoided disaster by responding like you were listening all along.

Remembering a phone number just long enough to dial it or rehearsing someone’s name just after they introduce themselves would be short-term memory. We can also manipulate details in working memory, like when we add 77 and 46 in our heads.

As you can see, cognitive scientists like to divide memory in many ways. Not surprisingly, memory is an enormous field of study — we could spend months exploring it and still not cover everything.

But in this article, we’ll narrow the scope a little by focusing on long-term memory. How do we get them into and out of the brain?

But before we get to that, let’s review…

The Most Famous Patient in Brain Science

We can’t talk about memory without talking about Henry Molaison — you might know Henry as H.M.2

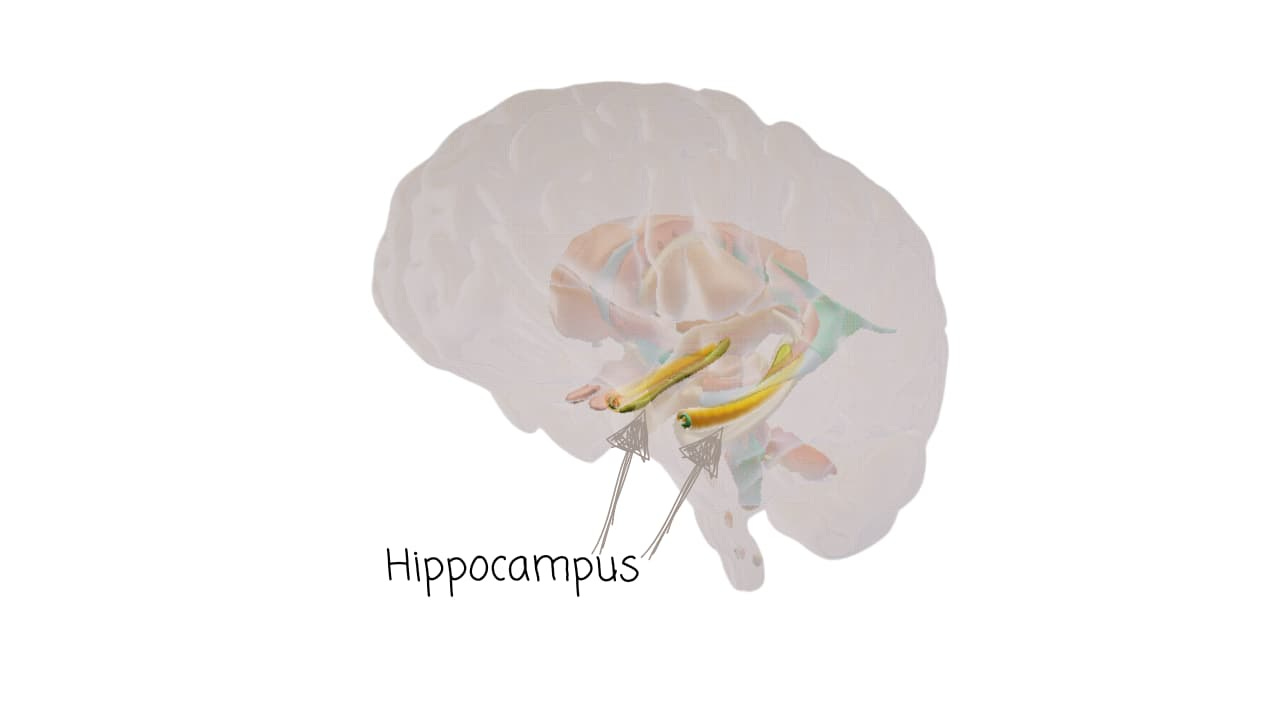

When Henry was just 27, he underwent experimental brain surgery to treat his severe epilepsy. The surgeon removed portions of his temporal lobes, including parts of his hippocampi, amygdalae, and surrounding areas. While the surgery successfully treated his epilepsy, it had some unexpected consequences.

The surgery left Henry unable to form new episodic memories. He couldn’t remember new experiences that happened after his surgery — he couldn’t even remember people he’d just met moments ago. Interestingly, he sometimes showed fleeting semantic memory that he could have only learned after his surgery. For example, he mentioned astronauts by name or the Beatles, but these memories were unstable — he couldn’t reliably retrieve them.3

Remarkably, he could still learn new physical skills. He would play puzzles and perform tasks each day. He wouldn’t remember doing the puzzles or tasks, but he would get better at doing them. Each time he was shown the puzzle or heard instructions on how to perform a task, he’d say he’d never done it before.

H.M.’s case suggested two things about memory.

One. Our ability to remember facts (semantic memory) and experiences (episodic memory) is not the same as our ability to remember skills (procedural memory).

In other words, there is a difference between memory we can consciously declare and memory that is accessed without conscious thought. Henry’s brain surgery had taken his declarative memory while leaving his non-declarative memory intact.

The second thing is that Henry did not lose everything about declarative memory. He lost his ability to gain new episodic memory, and his ability to form new semantic memory was severely restricted. But he could still remember old declarative memories from before the surgery.

Henry’s case suggests that getting memories into the brain might not be the same as getting them out.

Let’s start with…

Q2: How Do We Get Memories into the Brain?

When we form new semantic and episodic memories, many different areas are active.

Imagine you’re experiencing coffee for the first time. Your visual cortex would process how the coffee looks. Your auditory cortex would take in the sound of the coffee being poured. Your olfactory cortex would process the aroma. When you take a sip, areas that process taste and temperature are active.

But forming a memory isn’t just about sensory input. You need to encode what the thing is (that this is coffee, a drink). And you also need to encode where and when you’re experiencing the coffee (perhaps a particular café on a cold morning). This what and where information is dealt with by different pathways in the brain.

But how does the brain form the new memory?

At the cellular level, when you’re learning something new, like experiencing coffee for the first time, the connections between neurons (called synapses) change their strength. For long-term memory, brain cells actually sprout tiny new branches — like trees growing new twigs. These changes lead to the growth of new connections between brain cells. At a molecular level, specific proteins and other cells, like astrocytes, play a role in memory formation by promoting these synaptic changes.4

When discussing memory, the hippocampus takes centre stage. While it’s probably the most famous brain region associated with memory, its exact role is still debated. In terms of getting memories into the brain, semantic and episodic memory both seem to require the hippocampus. But as we’ll see, that might not be the case for getting memories out of the brain.

Q3: How Do We Get Memories Out of the Brain?

As I mentioned earlier, we don’t get memories out of the brain like retrieving a file from a computer. Instead, we reconstruct them — we create memories anew each time we remember.

But how does this reconstruction process work? And what role does the hippocampus play? Different theories suggest the hippocampus performs different jobs for different types of memories.

According to the traditional view, all our memories initially need the hippocampus. But this doesn’t mean memories are stored in the hippocampus — instead, it might act more like an encoder or coordinator, helping different brain regions work together to create memories. Over time, through a process called consolidation, memories become established in other parts of the brain. After a few months, the theory suggests, we no longer need the hippocampus to remember these experiences or facts.

It’s worth noting that traditionally, much of what we knew about memory came from studying people with brain damage, like H.M. For decades, scientists believed H.M.’s case supported the traditional view — the hippocampus was necessary for forming new memories but not for retrieving old ones. Since his surgery had supposedly removed his hippocampi completely, it made sense that Henry could remember old memories but not form new ones.

But when researchers examined Henry’s brain after his death, they discovered that about half of his hippocampal tissue had survived the surgery.5 It’s difficult to tell whether the remaining tissue was functional, though. It’s possible it may not have been functional since it was disconnected from most other brain regions. But, in either case, this finding reminds us to be cautious about drawing definitive conclusions from individual case studies.

The brain is incredibly complex, and damage is rarely as clean or precise as we might like for our theories. This is why modern memory research relies on multiple approaches — from case studies to brain imaging to animal research — to piece together how memory works.

It may not be surprising, then, that recent research challenges the traditional view. The new theory — multiple trace theory6 — suggests there’s a difference between semantic and episodic memories. While semantic memories eventually become consolidated in the cortex and don’t need the hippocampus for retrieval, episodic memories continue to rely on the hippocampus for retrieval, even after consolidation. This suggests that episodic and semantic memories might be independent — at least when it comes to retrieving those memories.

One way to think about this is to consider how we learn new things.

When you think about it, everything we initially learn comes through experience — it’s all learned through events.7 Whether we’re sitting in a classroom learning that the Earth revolves around the Sun, having our first taste of coffee, or experiencing our first kiss — these are all events.

But later, when we remember things, there’s a difference. For most of us, the memory that the Earth revolves around the Sun has been detached from our memory of learning it. We might remember the fact but not where we were or who taught us this fact.

But that first kiss? We remember that differently. We remember where we were, who we kissed, and maybe even what we were wearing or what song was playing.

This distinction between semantic and episodic memory brings us back to Mary, our brilliant scientist in the black-and-white room. Mary could accumulate endless semantic memories about colour — facts about wavelengths, how the retina processes light, and how the brain responds to different colours. She formed these semantic memories through her experiences of reading, studying, and watching her black-and-white television. She would have episodic memories of learning some of these facts — she might remember specific moments reading a particular book or watching a particular program.

But while still in her room, she couldn’t form episodic memories involving the experience of colour itself. She wouldn’t remember the first time she saw a red rose or a blue summer sky because she never had those experiences.

This raises an intriguing question: if all our learning initially comes through experiences, why do some memories become detached from their original context while others remain firmly tied to when and where we learned them?

Next Week…

If you think emotion has something to do with why some memories become detached facts while others remain vivid, then I think you’ll enjoy next week’s article.

Why do we remember where we were when we heard about 911 — but not where we were when we learned that the Earth revolves around the Sun? Why do most of us remember our first kiss in vivid detail — but not our first algebra lesson?

The fact that our most emotional experiences tend to be our most vivid memories suggests that there might be something special — perhaps even necessary — about emotions for episodic memory.

Next week, let’s explore these questions by reviewing the movie Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. In this movie, characters choose to erase painful memories of a past relationship.

Is science getting closer to giving us control over what we remember — and what we forget? And if so, should we do it?

Thank you.

I want to take a small moment to thank the lovely folks who have reached out to say hello and joined the conversation here on Substack.

If you’d like to do that, too, you can leave a comment, email me, or send me a direct message. I’d love to hear from you. If reaching out is not your thing, I completely understand. Of course, liking the article and subscribing to the newsletter also help the newsletter grow.

If you would like to support my work in more tangible ways, you can do that in two ways:

You can become a paid subscriber

or you can support my coffee addiction through the “buy me a coffee” platform.

I want to personally thank those of you who have decided to financially support my work. Your support means the world to me. It’s supporters like you who make my work possible. So thank you.

Penfield, W. (1952). Memory mechanisms. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry, 67(2), 178–198. DOI: 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1952.02320140046005

Corkin, S. (2013). Permanent present tense: The man with no memory, and what he taught the world. London, UK: Allen Lane.

Dittrich, L. (2016). Patient H. M.: A story of memory, madness, and family secrets. London, UK: Chatto & Windus.

Asok, A., Leroy, F., Rayman, J. B., & Kandel, E. R. (2019). Molecular mechanisms of the memory trace. Trends in Neurosciences, 42(1), 14–22. DOI: 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1952.02320140046005

Annese, J., Schenker-Ahmed, N. M., Bartsch, H., Maechler, P., Sheh, C., Thomas, N., ... & Corkin, S. (2014). Postmortem examination of patient H.M.’s brain based on histological sectioning and digital 3D reconstruction. Nature Communications, 5, Article 3122. https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms4122

Nadel, L., & Moscovitch, M. (1997). Memory consolidation, retrograde amnesia, and the hippocampal complex. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 7(2), 217–227. DOI: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80010-4

Well, this isn’t strictly true — we’re born with some innate knowledge and capabilities. But for the purposes of this discussion about memory formation and retrieval, I’ve focused on the things we learn through experience.

This is fascinating! When you consider how much a person’s personality and daily function depends on their memory, you have to ponder the mystery of what a person actually is at the most basic level…

Well I guess I still recognise much if not all of this - I am surprised by this more than I can convey.

It is a marvellous and succinct treatment which gives the new student a great framework on which to build. Like I remember saying previously, I do wish that I had read or heard you lecture (presumably through some space time anomaly - like Kevin Costner in the film about the radio broadcast across time!) when I was a student way back. It would have saved me a lot of trouble and confusion (with some errors thrown in for good measure).

Filmic fantasies and allusions aside, I do wonder how you manage to maintain such a high standard and communicate so well. Just luck, brains and toil, I guess. Thanks Suzi.