The Code that Cures Blindness

BCI #2: Optogenetics, Math, and a Vision for Our Future

Welcome to Part 2 of our brain-computer interface (BCI) series. Last time, we briefly reviewed some of the different approaches researchers are taking to explore BCIs and we discussed how the cochlear implant works.

This week, I want to explore how scientists are using BCIs to restore vision to the blind. BCI researchers have pursued various approaches to restore vision, but this week, I'll focus on one particular method that holds significant promise. This approach involves a fairly new scientific technique called optogenetics, as well as math and computer power to restore sight to the blind. Of course, this work is exciting for humans, but, as we will see, it also has intriguing implications for computer vision.

This week we’re asking three main questions:

What is Optogenetics?

Why Code Could Cure Blindness? and

How Does Understanding Human Vision Help Computer Vision?

But first, for those who need a refresher, let’s review:

How the eye works and

What causes blindness?

How does the eye work?

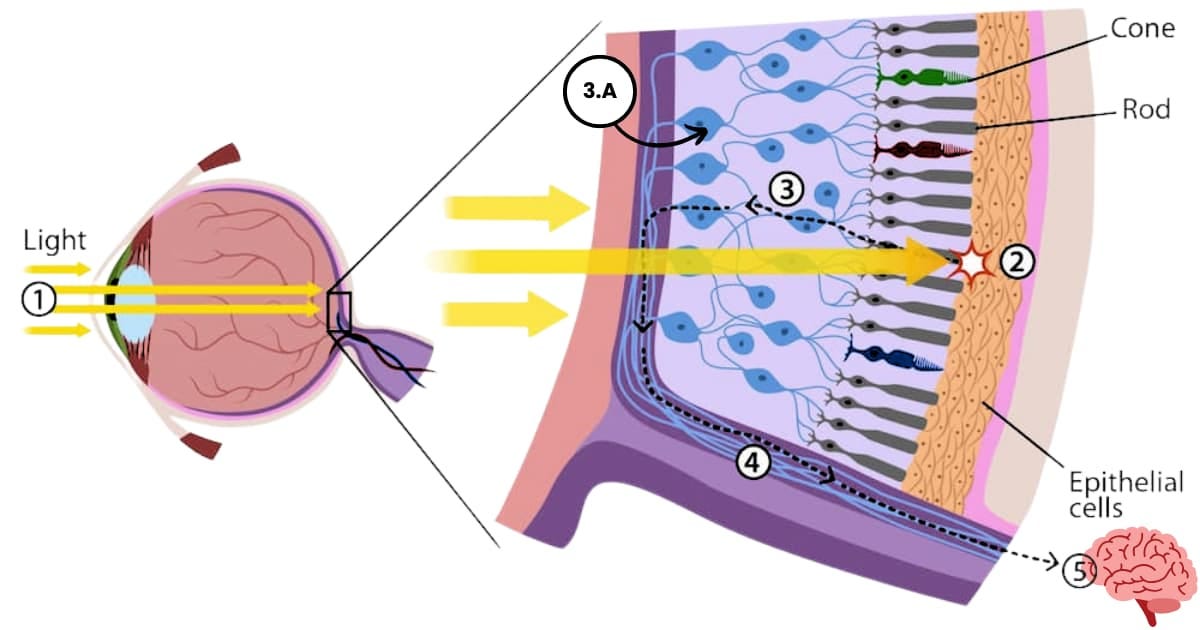

Figure 1 is a simple schematic of the human eye. Light enters the eye through the cornea and pupil (step 1) and is focused by the lens onto the retina at the back of the eye (step 2). The retina contains specialized photoreceptor cells called rods and cones, which are sensitive to light. Rods detect light and dark, while cones detect colour.

When light hits the photoreceptors, it initiates a biochemical process that converts the light into electrical signals. These signals travel through several layers of interconnected nerve cells within the retina (step 3) before reaching the ganglion cells (step 3A). The ganglion cells collect and integrate the signals and transmit them along the optic nerve (step 4) to the brain (step 5), where visual information is processed further, allowing us to perceive the world.

We used to believe that the eyes were passive — light would enter the eye, and information would be passively passed onto the brain for processing. However, scientists have recently discovered that the eye actively processes information before it gets to the brain. It is now thought that cells in the retina work as a pre-processor, analyzing and modifying the signals from the photoreceptors before they are sent to the brain. These intermediate cells turn the information from the photoreceptors into code the brain can understand.

What causes blindness?

According to the World Health Organization, the leading causes of blindness are uncorrected refractive errors and cataracts. However, blindness can also be caused by damage to the retina, the optic nerve, or the brain areas responsible for vision processing.

In this article, I will focus on treatments for damage to the retina, such as macular degeneration and retinitis pigmentosa, because these treatments have seen the most exciting advancements in the past few years.

Macular degeneration is a disease that damages the macula, the central portion of the retina responsible for sharp, straight-ahead vision used for reading, driving, and recognising faces. Over 200 million people worldwide are affected by macular degeneration.

Retinitis pigmentosa is a group of rare inherited diseases that causes progressive degeneration of the photoreceptor cells. Over time, this leads to gradual vision loss and potentially complete blindness. Retinitis pigmentosa affects about 2.5 million people worldwide.

Both macular degeneration and retinitis pigmentosa occur when retinal cells become damaged or die prematurely. Once the photoreceptor cells die, cells in the interconnected layer (step 3 in Figure 1) usually die too, but the ganglion cells remain intact.

The problem with not having working photoreceptors is that, unlike photoreceptors, ganglion cells don’t respond to light. You can shine a light directly into an eye without working photoreceptors, and the ganglion cells will remain quiet — the brain will not receive visual information about the world.

Well, that’s how normal ganglion cells work. But scientists have figured out a way to make ganglion cells not so normal — they figured out how to make ganglion cells respond to light.

Q1: What is Optogenetics?

In Part 1 of this series, I mentioned a popular BCI method for getting information into the brain: stimulating cells with electrodes. To stimulate ganglion cells, a surgeon can implant electrodes into the retina.

But this sort of approach has a problem: It lacks spatial precision.

One electrode could stimulate anywhere from 1,000 to 5,000 ganglion cells. In the retina (and the brain) cells responsible for opposing effects often sit right next to each other. So, stimulating thousands of cells will likely stimulate the cells of interest and other cells with opposing effects (that we don’t want to stimulate).

Back in 1979, Francis Crick — the co-discoverer of the molecular structure of DNA who later shifted his research focus to neuroscience — understood this problem of a lack of spatial precision. He set a challenge to find a technology that would allow neuroscientists to control specific neurons without affecting other populations of neurons. He suggested this magical technique might be done with light.

At the time, Crick’s idea seemed like pure science fiction. But it is now a scientific fact called optogenetics.

The key to optogenetics lies in light-sensitive proteins called opsins. Opsins are found in the visual systems of all animals, but for optogenetics, scientists use opsins from a wide range of organisms, including bacteria and single-celled algae.

Scientists can isolate the genes responsible for making cells sensitive to light and then put those genes into cells using gene technology. If they put specific opsins into specific cells, researchers can use light to turn on or off specific cells. By shining different wavelengths of light, they either make a cell fire or stay quiet with both spatial and millisecond precision.

Optogenetic research is moving quickly. The first study demonstrating the optogenetic effect was published in 2005. It showed the effect in cultured neurons (neurons in a petri dish). In 2007 optogenetics was being used in mice studies. By 2009 the method was being applied to almost all cell types. In 2012, scientists could activate single cells with light-guided strategies. In 2019, scientists were able to specifically control up to 50 individual neurons in a mouse brain which could bias the decisions the mouse would make. In 2022, scientists could control hundreds of neurons with specific instructions for each cell in the visual cortex of a mouse brain. And in 2024, we are seeing research advance towards combining robotics with optogenetics to restore lost movement in individuals with neurological conditions such as paralysis.

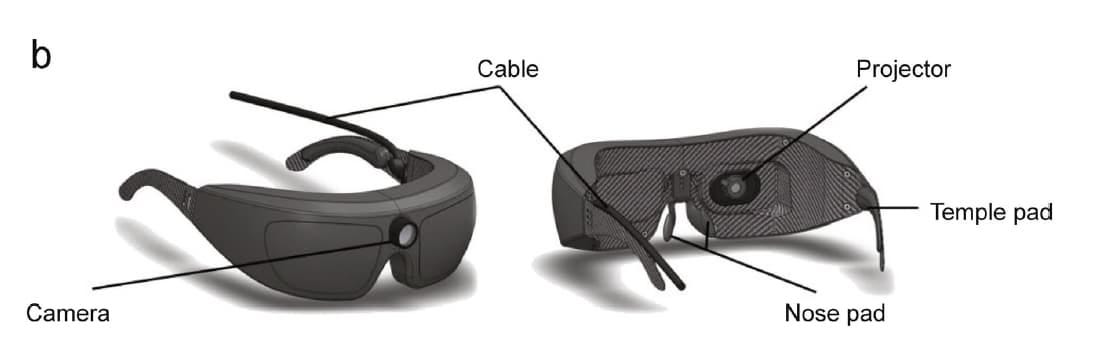

In 2021, a group from the University of Basel, in Switzerland, performed the first optogenetics on a human. The patient suffered from retinitis pigmentosa and was considered to be legally blind in both eyes. Opsins were injected into one eye. And four months after the injection, the patient started training with light-stimulating goggles (see Figure 2). The goggles had a camera that detected light changes in the world and projected those changes onto the treated retina. About seven months after training began, the patient showed signs of improved vision. When using the goggles, the patient could point to, count, reach for, and touch objects he previously could not see.

Q2: Why Code Could Cure Blindness?

The results from the Switzerland group are amazing. But that’s just the beginning!

Neuroscientist Sheila Nirenberg from Cornell University is working on a way to restore lost vision that could have a profound impact. Her approach aims to go beyond restoring functional vision to the blind. She believes she can actually restore vision beyond normal human capabilities. In other words, Nirenberg's work could potentially allow the blind to see better than someone with normal healthy 20/20 vision.

In the section above on how the eye works, I mentioned that scientists now think that cells in the retina act like a preprocessor, turning light information into code that the brain can understand. According to Nirenberg, without these retinal cells, light projected onto the ganglion cells—even when those ganglion cells are genetically modified with optogenetics—will likely receive code that the brain finds difficult to understand.

To us, brain code looks like patterns of pulses — sometimes called spiking patterns. Understanding how to transform our visual world into these seemingly unintelligible spiking patterns has been a mystery. But Sheila Nirenberg has figured it out. This was such a genius breakthrough that she was awarded the MacArthur Genius Award for this work.

Nirenberg’s current work combines the ability to transform the visual world into brain code with the precision of optogenetics.

Like the group in Switzerland, blind patients in Nirenberg’s clinical trial receive optogenetics treatment and use goggles with a camera that detects changes in the visual world. However, these goggles contain an encoder that converts information from the camera into brain code. This brain code is then converted into specific patterns of light pulses and projected onto the ganglion cells. Unlike previous approaches that stimulate many ganglion cells with electrodes, Nirenberg's system translates images into brain code stimulating precisely the cells that need to be stimulated.

Which is super cool, but does it work?

At the last update, 12 patients had received low-dose treatment. Initially, these patients could not see at all, or their vision was so poor they were almost completely blind. Before treatment, one patient was asked to report the direction a line was moving (to the right or the left). The patient responded, “I can’t even tell you there is a line, let alone what direction it is moving.”

Amazingly, about 6 to 8 weeks after receiving the optogenetic injection into one eye, patients reported seeing light from the treated eye. Even without using the goggles! One patient reported seeing the light from Hanukkah candles, and another reported seeing their dog running in the snow. The details, of course, were missing, but to go from being completely blind to being able to see light and movement even without wearing the goggles is simply amazing.

At 3 months after optogenetic treatment, patients were tested with the goggles. Light sensitivity and motion detection had improved dramatically.

None of the patients were able to identify objects, yet. But there are likely a few reasons why this might be the case:

These patients were given a low dose of the treatment. Earlier work in mice shows that higher doses produce a non-linear improvement in vision, meaning vision will likely improve substantially with higher doses.

Optogenetics is known to improve light sensitivity over time. Thus, despite the low-dose treatment, patient vision will likely improve with time.

The patients did not train with the goggles—for this trial, only one pair of goggles was used by all the patients and only during testing. It is likely that with extensive use, the brain will get even better at interpreting the input from the goggles.

Some of the exciting findings from this research suggest that goggles may not be needed for people with early-stage blindness who still have some photoreceptors and intermediary cells intact. Vision might happen somewhat normally, with an optogenetic treatment to genetically modify the ganglion cells, making them directly responsive to light. This approach is particularly promising for diseases like retinitis pigmentosa, where peripheral vision often remains intact longer. Unfortunately, degeneration of retinal cells will continue, and the patients will likely eventually need to wear goggles, but it might be a way to improve vision for longer.

Superhuman vision?

Beyond restoring lost vision to normal healthy levels, this technology has the potential to enhance vision to superhuman levels. Optogenetics could be designed to make certain neurons respond to ultraviolet light (like bees) or infrared light (like mosquitoes). So, there is the potential to reverse blindness so that those who were once blind can see wavelengths of light beyond what we consider the human visible light spectrum. While this is theoretically possible, it's still in very early research stages.

Q3: How Does Understanding Human Vision Help Robot Vision?

An interesting consequence of Nirenberg's research is that it provides a new way to do computer-based vision. Incorporating a pre-processing stage similar to biological vision into computer vision algorithms could enable robots to solve visual problems more effectively.

In other words, computers could solve vision problems similarly to humans and other biological creatures — generalising understanding to many different situations in a non-rule-based way. For instance, just as we can quickly spot a moving vehicle, estimate its speed and decipher whether it is a car, a truck, or a bicycle, under different lighting conditions, these algorithms could help machines better identify objects under varied conditions, too. It also means that the amount of data required to train the algorithms is much less than with traditional deep learning algorithms.

Nirenberg has decided to spend her time working on restoring lost vision for the blind. Her second company, which focused on computer vision, was sold to Intel. Intel is using the technology to improve computer vision for Mars robots, surgery robots, self-driving cars, and shoplifting detection, among other uses.

Thanks so much for reading this article.

I want to take a small moment to thank the lovely folks who have reached out to say hello and joined the conversation here on Substack.

If you'd like to do that, too, you can leave a comment, email me, or send me a direct message. I’d love to hear from you. If reaching out is not your thing, I completely understand. Of course, liking the article and subscribing to the newsletter also help the newsletter grow.

If you would like to support my work in more tangible ways, you do that in two ways:

You can become a paid subscriber

or you can support my coffee addiction through the “buy me a coffee” platform.

I want to personally thank those of you who have decided to financially support my work. Your support means the world to me. It's supporters like you who make my work possible. So thank you.

Brilliant article. I hadn’t realised such progress had occurred. Thank you.

Not so long ago, I listened to a 99% Invisible podcast episode "The Country Of The Blind" which was an interview with Andrew Leland who wrote a book of the same name, based on his experience with gradually going blind due to a medical condition.

The inevitability and permanence of his upcoming full blindness was never in question.

It's amazing to see that there's a non-trivial chance that blindness may be curable in the future.