Could Entropy Explain Consciousness?

Information and Complexity: Essay 4

You woke up today older. Not younger.

You remember yesterday, but tomorrow is a blank page.

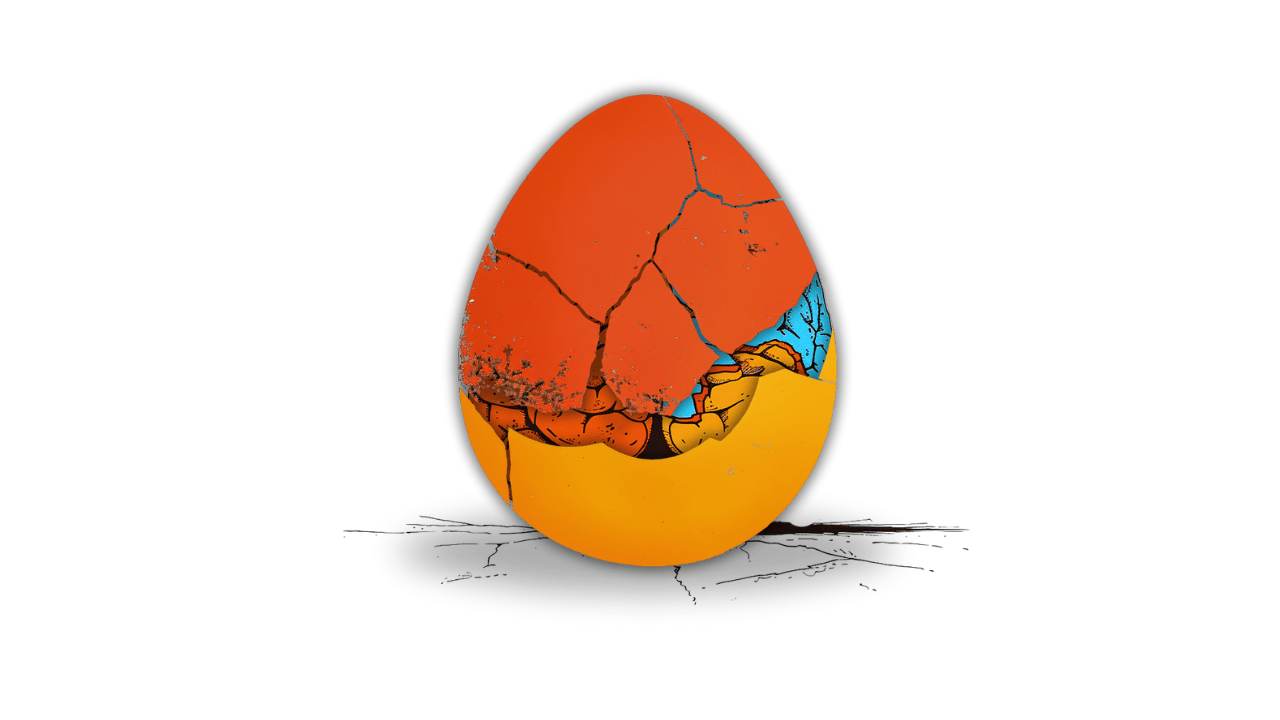

In your time on this earth, you’ve seen your fair share of eggs breaking, leaves falling, and cream mixing into coffee. But you have never seen an egg unbreak, a leaf leap back onto its branch, or cream separate itself from coffee.

Of course, you say. Because time moves forward. Everything moves forward. That’s just the way it is.

Physicists call this forward march of time the arrow of time, and it’s everywhere.

Left alone, ice melts, hot coffee cools, your favourite t-shirt fades, the autumn leaves turn to red and gold, and the universe continues its accelerated expansion.

It sounds poetic, but it’s just the second law of thermodynamics.

Over time, entropy tends to increase. Over time, things tend to move from order to disorder.

On their own, with enough time, it is more probable that ice will melt, coffee will cool, your favourite t-shirt will fade, and the leaves on your backyard tree will turn gold. More probable, that is, than water freezing on its own, cold coffee warming itself on its own, your favourite t-shirt restoring its colour, or dead leaves catching the breeze and painting themselves green once more.

Time’s direction feels inevitable. There is a seemingly obvious difference between the past and the future.

But why is the direction of time inevitable? Why doesn’t time move backwards? or not at all?

For reasons we don’t yet fully understand, nearly fourteen billion years ago the universe began as a hot, dense, ordered state. Then it started expanding.

And ever since, entropy has been increasing.

This is sometimes referred to as the Past Hypothesis — the idea that the universe began in a low-entropy state.

That simple fact — that entropy was lower yesterday than it is today and it was lower a year ago than it was yesterday — is what physicists think defines the difference between past and future.

It’s why that once-crisp image on your favourite band tee has faded, much like the memory of the day you bought it.

The arrow of time — the fact that time has a direction — started with the Big Bang.

But here’s the thing about time: nothing in the fundamental laws of physics says it must move in this direction. The equations that govern motion, gravity, and quantum mechanics don’t care which way time flows. If you watched the universe in reverse, the math would still work. The laws of physics are time-symmetric. They don’t distinguish between past and future.

So, at the microscopic level — at the scale of individual atoms and molecules — individual particles don’t have a built-in direction for time. But this is not true at the macroscopic level — the everyday scale which we experience.

At the macroscopic level, time seems to only have a play button. There doesn’t seem to be a rewind. At the macroscopic level, mixed coffee does not spontaneously separate into cream-on-top coffee. And broken eggs don’t reassemble themselves.

According to our best theory of physics, time’s direction is not a fundamental property of the universe. It’s an emergent one. It is something that arises only when we look at macroscopic level.

A strict reductionist might argue that if the microscopic laws are time-symmetric, then time’s arrow is just an illusion — a kind of trick — something that vanishes if we analyse reality at a fine enough scale.

Einstein, too, questioned our intuitive sense of time’s passing. He famously wrote, “the distinction between past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.” It sounds mystical, but in context, he was making a point about relativity: from that perspective, time doesn’t flow. All moments simply exist — like locations on a map.

But our experience feels otherwise — the direction of time seems real with real consequences.

So, we might want to ask — if it’s a trick — then what does this trick do?

What does the arrow of time give us?

To answer this question, we might want to consider what life would be like we didn’t experience time as moving forward — it simply stopped? It just held steady, locked in place from today onwards.

Well, for one, that band tee would finally stop fading. It would remain exactly as it is now — forever. Your hot coffee would never cool. The ice cubes in your iced latte would never melt. Autumn would never come. The leaves would never turn red and gold.

I’d miss autumn, but this doesn’t sound all that bad, so far!

But let’s keep going.

It’s true that things would never fall apart. But they would also never come together.

Rainclouds would never form. Seeds would never take root. Snowflakes would never crystallise.

If we didn’t experience the arrow of time, the world as we know it would be very different. Nothing would evolve. Nothing would come into existence. No growth, no decay, no difference between now, yesterday, and tomorrow.

That’s what the arrow of time is. It’s the unraveling of what was into what is, and what is into what will be. It’s our experience of entropy at work.

So, what does the arrow of time give us?

Everything interesting.

Not just fading band tees and melting ice cubes, but growth, structure, complexity, memories, and life.

And those are all very interesting things.

But what is more interesting — what seems to be more shaped by time’s arrow — than experience itself?

William James famously described experience as a stream of consciousness — a continuous, unfolding flow. Our memories, perceptions, and thoughts evolve from moment to moment.

But what is a moment without a direction in time? What is a stream that doesn’t change?

Some suggest that consciousness might be possible without time’s direction. Those who meditate sometimes describe something like this — a state of simply being, without thoughts or any perception of time — but for many of us, it’s difficult to imagine what that would feel like.

For many, it’s difficult to imagine what a sense of self would be like — or a conscious thought existing at all — without a direction in time.

What do you think?

If we didn’t experiencing a direction in time, could we simply be — without context, without narrative?

Next week…

Sometimes, we hear that complex things like life and consciousness are exceptions to entropy. That complexity pushes back against the universe’s natural drift toward disorder.

But what if complexity — things like life and consciousness — are not exceptions to entropy, but products of it?

Very good points Suzi! The way entropy has historically been presented is as something bad. And for the engineers who discovered it, it was. But it's really just a fact of existence. Without it, we would have a universe of perfect uniformity with no transformation, one without life or information. It's the inhomogeneities, the energy gradients, that make everything we care about possible. Entropy is both the enabler and doom of the universe. It both gives and takes.

Well I guess it might be a little like Billy Pilgrim and the Tralfamadorians in “Slaughterhouse Five” by Kurt Vonnegut. Great essay. Many puzzles.