Can AI Generate New Ideas?

On the origin of new ideas -- copying, combining, and curiosity

Hello Curious Humans!

I wasn’t planning on writing an article about the origin of new ideas. This week’s article was initially planned to be about an entirely different subject. But things took a turn while I was writing my initially planned article.

I had meticulously outlined, developed, and drafted what I thought was an original argument. But as I was making the final revisions, a leading scientific journal released an article that, to my dismay, laid out an argument strikingly similar to the one I had so painstakingly formulated. What I thought was an original thesis had been preempted.

How is it that two people on opposite sides of the planet arrive at the same idea within weeks of each other? Where do our ideas come from?

From popular books like Harry Potter to billion-dollar businesses like Apple or Amazon, we're taught that true innovation comes from forming new ideas. But are novel ideas achievable? or are new ideas simply clever remixes of existing ideas?

The stories, inventions, and works of art we hail as new ideas all contain traces of their inspirations and influences. Even revolutionary scientific theories are constructed from established scientific principles and past observations. So when is a new idea genuinely new?

This week in When Life Gives You AI, let’s put the idea of new ideas to the test by exploring three different situations in which we think we have a new idea. And for fun, let’s consider whether artificial intelligence (AI) can create these ideas.

Situations where we are mistaken — we mistake other’s ideas as our own

Situations where we remix existing ideas to create a new idea, and

Conceptual leaps — where we discover a new understanding of the world

But first, we should probably define what we mean by new ideas.

At first glance, the concept of an idea might seem simple to define, but it’s surprisingly difficult to pin down. Philosophers, psychologists, and thinkers have grappled with the concept for centuries. To avoid turning this article into a literature review on the concept of an idea, I thought I would simply use a dictionary definition. But the Cambridge Dictionary has four definitions:

idea

a suggestion or plan for doing something

an understanding, thought, or picture in your mind

a belief or opinion

a purpose or reason for doing something

While each of the dictionary's definitions captures an aspect of how we use the word idea, the second definition — an understanding, thought, or picture in your mind — is probably the best fit for what we’re exploring in this article. It’s more slippery than I would like, but let’s go with it for now.

And by new, I mean novel:

novel

new and original, not like anything seen before

Okay, let's ideate about ideas!

Situation 1: Mistaking Other’s Ideas as Our Own

We've all had that singular moment of brilliance — an ingenious idea that seems to materialise out of nowhere. But what if that original thought was actually an unconscious, unwittingly borrowed idea from someone else?

This puzzling phenomenon is known as cryptomnesia. We remember things — that’s what our brain does. We are exposed to many different ideas and often remember bits and pieces of these ideas. Later, those remembered ideas can resurface, and we feel like the idea was novel — it simply sprung from our minds. Cryptomnesia is not intentional plagiarism. We don't mean to pass off someone else's ideas as our own. It's simply a quirk of how our brain processes and prioritises information. We tend to remember the idea more than we remember the source.

As you can imagine, cryptomnesia can get you in trouble. There are numerous famous cases where creators were accused of accidental plagiarism. Helen Keller's celebrated story The Frost King contained remarkably similar elements to a work she had read years earlier as a child. Friedrich Nietzsche's seminal book Thus Spoke Zarathustra included passages almost directly lifted from the lesser-known philosopher Kurnberger's writings, to which Nietzsche had been exposed. And in the music world, George Harrison's smash hit My Sweet Lord drew legal sanctions for unconsciously borrowing substantial portions from the 1960s song He's So Fine.

Is cryptomnesia not strikingly similar to what generative AI does when generating content? Just as Keller's creation was influenced by prior exposure, AI models reframe existing information from their training datasets, producing outputs that echo previously established ideas. If so, can we claim that AI's outputs are new ideas?

On the one hand, it doesn’t seem fair to attribute Helen Keller as the originator of The Frost King. But on the other hand, she surely added her own ideas to the original story. The interesting question is, what did she add? And is what she added a fundamentally different thing from the parts she unknowingly copied?

Situation 2: Remixing of Existing Ideas

I recently asked Midjourney — the AI art generator — to imagine an original animal that no one has ever seen before. This was the response:

Initially, I thought, well, that’s funny. These look like new animals in one sense — I’ve never seen a bear elephant before. But in another sense, they look more like remixes of bits and pieces from animals (and plants) that I’ve seen before. Is a bear elephant really a new animal, or merely a remix of the existing concepts of bear and elephant?

Reflecting on the origins of our thoughts, it's hard not to think of the empiricist philosopher David Hume. Hume argued that we can only formulate a conceptual combination like bear elephant because we have previously seen and remembered the ideas of "bear" and "elephant.” For Hume, imagined ideas like a bear elephant simply come from rearranging simple ideas we've acquired empirically.

The AI-generated new animals are what Hume would call a complex idea — combining simple ideas the AI has gained during training. Given that Midjourney's training data likely contains many images of animals, plants, and virtually anything that can be photographed or illustrated, Hume would not have been too surprised by the results. Midjourney’s imagined creations are statistical remixes of its training dataset's various elements like textures, shapes, concepts and features. The novelty emerges from remixing those elements, not creating wholly new abstractions from nothing. Hume would likely view Midjourney's outputs as demonstrating the constraints of not only generative AI systems but also the constraints inherent in human thought.

When I first saw Midjourney’s response, I felt a bit smug. I assumed I had the uniquely human ability to be creative and imagine a new animal that was independent of my experience of the world. But then, I tried to imagine an original animal that no one had ever seen before that was not the remixing of existing animals. And I simply couldn’t do it. The only ideas I could come up with were strange combinations of existing animals. I’m not the most creative human, but I tried, and I simply couldn’t think of an animal that wasn’t the remixing of existing concepts. This article’s featured image of an octopus elephant is the peak of my imagination. But a quick Google Image search tells me I am not even the originator of this remix. The image below of an “octophant” is a fantastic creation by the street artist Alexis Diaz, which can be found on Hanbury Street off Brick Lane in London.

Generative AI, like large language models (LLMs) and AI art generators, excel at synthesising and remixing ideas from the datasets on which they’ve been trained. For example, LLM datasets contain an enormous swath of human knowledge, including literature, scientific papers, websites, and much more. This effectively makes LLMs extremely well-read—better read than any human we know.

Generative AI potentially has an advantage over humans when it comes to the remixing of ideas simply because of the sheer scale and breadth of information they can synthesise. For example, LLMs easily recombine ideas from millions of books, articles, websites, and other human knowledge artifacts. Their knowledge base easily exceeds what any single human could consume. This breadth of information might make their responses seem as though their creations are independent of their experience, but this might simply be because their responses are new to us. They are drawing from a huge dataset of information that we, as mere humans, could not possibly ingest, let alone assimilate.

Are all our ideas the remixing of simple ideas? Or is there something else we do that is not captured by the remixing of ideas?

Situation 3: Conceptual Leaps

A conceptual leap occurs when understanding advances so that previous ways of thinking are discarded in favour of the new idea. Consider Gregor Mendel's pioneering work on genetic inheritance in the 1860s. At the time, theories of heredity were vague and flawed. When Mendel systematically studied trait inheritance in pea plants, did he simply reconfigure existing concepts? His laws of segregation and independent assortment seemed to reveal entirely new biological principles.

What makes Mendel’s ideas seem like more than a remixing of existing ideas? We understand Mendel's ideas did not emerge in a vacuum. His work built upon concepts like species and varieties that had existed for centuries. However, through empirical experimentation, Mendel uncovered previously unknown ideas about how traits are passed from parent to offspring.

LLMs don't seem to discover like Mendel did. Their responses are confined to the boundaries of the existing knowledge in their training data. They can uncover patterns and relationships within that data, and those patterns and relationships might produce novel content, but they don't add knowledge to the dataset through empirical discovery or experimentation in the real world—they don’t do scientific discovery.

But is that the whole story? If we want to create generative AI capable of making conceptual leaps akin to Mendel's, is the solution simply to integrate LLMs with robotics? Is the primary obstacle preventing generative AI from achieving groundbreaking scientific discoveries through empirical research simply a matter of physical interaction with the environment?

Empirical discovery probably has something to do with it, but I think it is only half the picture. We need something else.

To generate his theory, Mendel needed to imagine alternative possibilities. He needed to ask why pea plants exhibit trait variations from generation to generation and what if these variations are predictably passed on.

In other words, he needed to be curious.

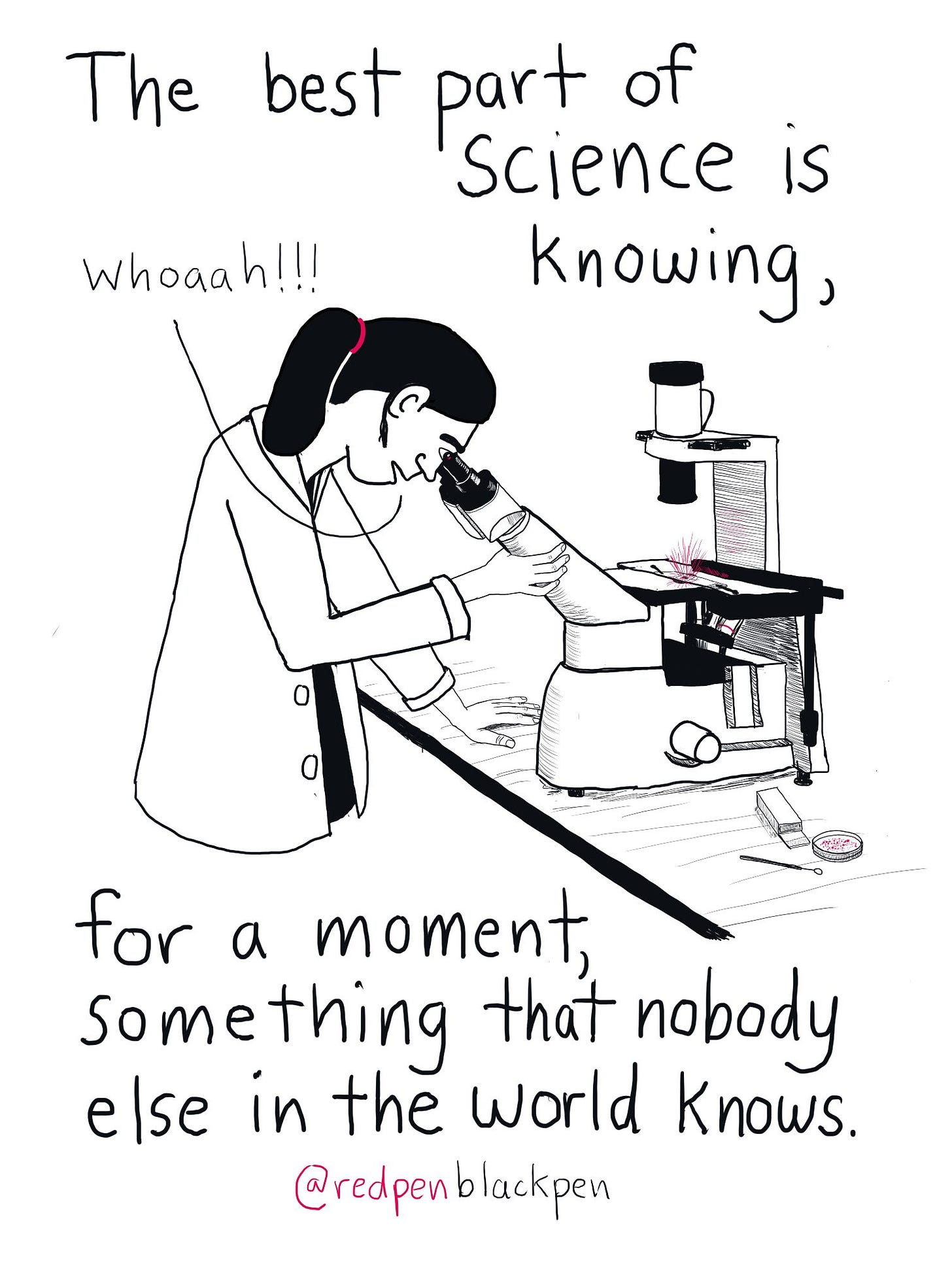

Curiosity was pivotal to Mendel’s theoretical breakthroughs. His ability to ask why? and what if? allowed him to explore beyond current understanding. This kind of curiosity — that questions current-day thinking — is what drives not only scientific discoveries but also creativity.

Progress, whether in the sciences, the arts, or any domain of human inquiry, hinges on curiosity. Consider 1905, the year Einstein published his Special Theory of Relativity. Einstein started with a what-if question: What if I could travel at the speed of light? How would the laws of physics apply? At the time, physics was primarily grounded in the theories of classical mechanics that had dominated for centuries. Einstein’s curiosity about the behaviour of light and time under extreme conditions and his what-if questioning were critical to his discoveries. Asking the right questions can lead to conceptual leaps.

Generative AIs aren’t motivated to ask why? and what if? Curiosity doesn’t drive them to explore unknowns and imagine alternative possibilities beyond a user’s questions and inquiries. They might seem curious when they find patterns in the data that are new and unique to the user, but they are not the driver of those inquiries… (well, at least not yet). For now, being curious — asking why and what if — might be uniquely human.

That isn't to say that Mendel and Einstein might not have benefited from access to LLMs — it’s possible that they would have found LLMs helpful tools in their discoveries. And it's conceivable that our most groundbreaking scientific discoveries are ahead of us, as the fusion of human curiosity with generative AI’s capacity to synthesise vast amounts of data could lead to unprecedented insights and innovations. But I’m not 100% convinced this is true, for reasons I will discuss in an upcoming article.

A short note to end this section…

I want to be clear that I’m not suggesting we need to acquire new empirical evidence for ideas and conceptual leaps. I think it is possible that conceptual leaps can be made by the remixing of existing knowledge. Indeed, Einstein did not gather new empirical evidence to formulate his Special Theory of Relativity. I do think empirical evidence and conceptual leaps might interplay well, though. If we want our ideas and conceptual leaps to be true ideas about the real world, we will want them to be logically sound and physically possible in the real world. We will want empirical evidence to support our ideas.

In many instances, empirical evidence gained through observing and experimenting in the physical world prompts us to rethink old theories and models. Finding something new in the world can be both the catalyst for new ideas and the confirmation of new ideas. So, while new empirical evidence is not necessary for new ideas and conceptual leaps, it can, and often does, challenge and expand our understanding.

The Sum Up

So why might two people from opposite sides of the world, without direct communication, simultaneously arrive at what appears to be a similar new idea? I think it has something to do with the collective zeitgeist — the shared environment that shapes our why and what-if questions. The published author and I have likely read similar work and been inspired by similar discussions, leading us to converge on a comparable insight. We simply asked similar why and what-if questions.

I put my initially planned article on hold because the ideas were so similar to the published article. I don’t think that the existence of the published article makes my article now worthless. But as writers, we want to contribute to the world of ideas. We want to say something new. This drive compels us as writers to seek out unique angles and fresh perspectives, even on well-trodden subjects. We want to remix ideas and imagine whys and what-ifs until we discover something new. We embrace the challenge of originality, the search for untold stories, unexplored implications, or innovative interpretations that can enlighten, inspire, or provoke thought in our readers. Even in a world rich with knowledge, a curious writer seeks the undiscovered — the gems at the edges of what is known.

I will publish my original article, although it won’t be the original. I now have a few new why and what-if questions to answer.

Here are three interesting articles I’ve read this week:

By

By

By

These are great insights on originality of ideas and creations, Suzi! I’d like to reference it in my new article series on ethics of generative AI for music, if that’s ok?

David Deutsch has a great conversation with Naval about how LLMs will never be fully creative because, definitionally you’re constraining their outputs, and they’re never allowed to ask why. Only by letting them question and get stuff wrong will they arrive at human level general intelligence

Rick Rubin has a much more wuwu interpretation of creativity which I resonate with as well

https://open.substack.com/pub/matthewharris/p/deep-dive-the-creative-act-a-way?r=298d1j&utm_medium=ios

Thanks for another great article!