We humans love thinking about what is possible. We wonder about all sorts of things — is it possible to travel at the speed of light? Is it possible to create artificial intelligence that understands human emotions? What would the world look like if Hitler wasn't born or if the dinosaurs had never gone extinct? Is it possible for humans to live forever or to colonise other planets? Could we one day communicate telepathically, or could a dog learn to read?

In philosophy, to explore what is possible, philosophers turn to thought experiments — those made-up scenarios designed to test our intuitions and challenge our assumptions.

Imagine a zombie — a creature physically identical to a human but lacking consciousness. Or picture a scientist named Mary who lives in a black-and-white room and has never experienced colour. Scenarios like these rely on our ability to imagine novel situations and ask us to question whether they are possible.

But this raises interesting questions. Is our ability to conceive ideas a reliable guide to what is possible? Or are there limits to our conceptions?

To find out, let's ask three questions:

What do we mean when we say something is possible?

What do our conceptions reveal about what is possible? and,

Are there limits to our conceptions?

This article is the first in a series on the key thought experiments in the philosophy of mind. In future posts, we'll explore specific thought experiments and ask questions like, could an entity physically identical to you lack consciousness entirely? And what happens when a colour expert sees red for the first time?

Q1: What Do We Mean When We Say Something is Possible?

When we think about what is possible and what is not possible, sometimes a simple dichotomy doesn't work. Sometimes, we don't just want to claim that something is either possible or not possible. Sometimes, we want to include some conditions or qualifications in our claims.

For example, we might like to say that it's logically possible for a human to run a mile in under a minute, even though it's probably not physically possible, given our current biological limitations. Or we might say that it's possible for water to remain liquid at -10°C, but not in our world under normal atmospheric pressure.

So, there's some nuance to possibility.

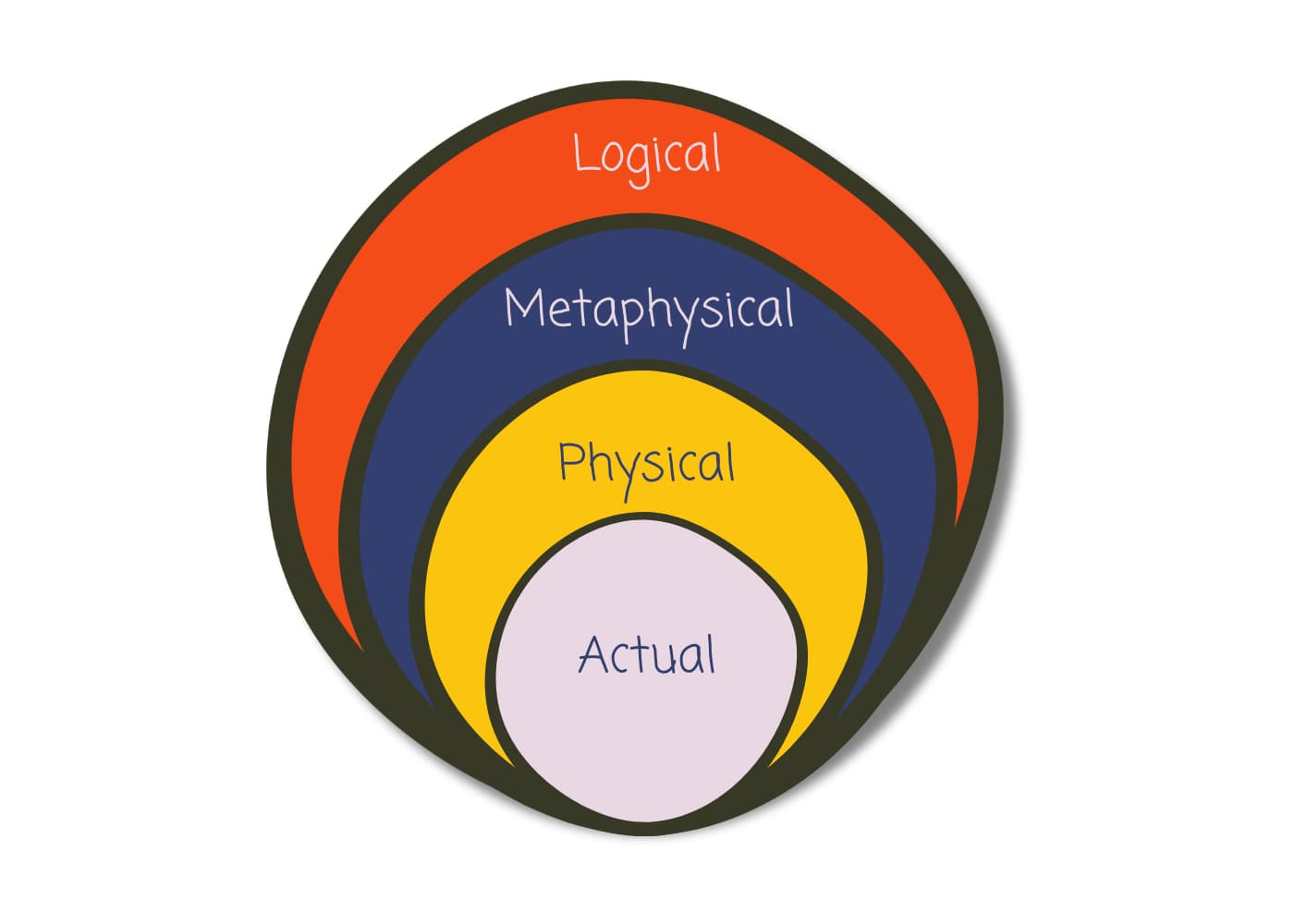

Philosophers have identified three main categories of possibility: logically possible, physically possible, and metaphysically possible.

Let's break them down.

Logically possible

Logical possibility is the broadest form of possibility. Something is logically possible if it doesn't violate the laws of logic, even if it might not exist in our world.

For example, in the movie Star Wars, the idea of spaceships travelling at the speed of light is logically possible.

We can construct a logical argument for this:

Premise 1: In the Star Wars universe, spaceships are equipped with hyperdrive technology.

Premise 2: Hyperdrive technology allows for faster-than-light travel by propelling spaceships into hyperspace, where the constraints of normal space-time do not apply.

Conclusion: Therefore, in the Star Wars universe, spaceships can travel at the speed of light (or faster) due to their hyperdrive technology.

This argument is logically valid — the conclusion logically follows from the premises.

On the other hand, if we were to claim that it is the case that Darth Vader is Luke's father and it is also the case that Darth Vader is not Luke's father — that would not be logically possible. Darth Vader can't be both Luke's father and not Luke's father at the same time.

Logical possibility is the foundation for all other types of possibility, but it doesn't tell us anything about whether something is actaully possible in the real world. It's merely a statement about whether an idea or concept can be described without logical contradiction.

Physically Possible

Physical possibility is more constrained than logical possibility. Something is physically possible if it doesn't violate the laws of physics in our universe.

For example, while spaceships travelling at the speed of light might be logically possible (as we can describe them without contradiction), they are not physically possible in our world, given our current understanding of physics.

If a spaceship like the Millennium Falcon were to travel at the speed of light in our universe, it would encounter severe problems:

It might be pulled into a black hole, as nothing (including light) can escape a black hole's event horizon.

To avoid this, it would need to travel faster than light, which is even more of a problem.

So, we can say that faster-than-light travel is logically possible (we can imagine and describe it without contradiction), but it's not physically possible given the laws of physics as we currently understand them.

While most agree that what is physically possible is broader than what is actual, not everyone accepts this idea. Some argue that what is physically possible is what is actual (but we’ll leave that debate for another day).

Metaphysically Possible

Metaphysically possible occupies a space between logical and physical possibility. It doesn’t restrict what is possible to what is actual or even what is physically possible in our current universe — it includes what is possible in other worlds, too.

When philosophers talk about other worlds, they're not referring to alien planets or parallel universes in the science fiction sense. Instead, they're talking about logically possible alternatives to our actual world. These are complete and coherent ways the entire universe could have been different. For example, a world where the laws of physics are slightly different or where historical events unfolded differently would be considered other worlds in this philosophical sense.

Questions about what is metaphysically possible pop up in philosophical debates about the nature of reality, free will, personal identity, and, of course, consciousness. Thinking about what is metaphysically possible is particularly relevant in thought experiments, where we are asked to consider a situation that is beyond our experiences.

So why consider the metaphysically possible?

The argument goes: If we limit ourselves to only logical and physical possibility, we could make statements that are either logically true but might not say anything about our world or physically true about our current universe. But this approach, proponents argue, leaves no room to discuss what could be, what might have been, or how things might be in the future. Metaphysical possibility fills this gap. It supposedly allows us to explore alternate realities and consider how aspects of our universe could be different.

The idea that facts could be metaphysically possible is controversial. Some philosophers question whether it's meaningful to think about facts distinct from what is logical or physically possible.

But even if you think the category has some value, you might be wondering — how the heck do we determine what is metaphysically possible?

Unlike physical possibility, we can't directly observe or empirically test metaphysical possibilities. We're dealing with what could be true in another possible world beyond our physical reality.

Q2: What Do Our Conceptions Reveal About What is Possible?

One of the most influential ideas about how we can discover metaphysical possibilities comes from philosopher David Hume. In his work, A Treatise of Human Nature, Hume claims there is a link between what we can conceive and what is possible:

’Tis an establish’d maxim in metaphysics, That whatever the mind clearly conceives includes the idea of possible existence, or in other words, that nothing we imagine is absolutely impossible. We can form the idea of a golden mountain, and from thence conclude that such a mountain may actually exist. We can form no idea of a mountain without a valley, and therefore regard it as impossible.

In other words, if we can clearly conceive or imagine something, we have reason to believe it is possible. This doesn't necessarily mean it's possible in our world, but that it's not absolutely impossible in all possible worlds.

Hume's maxim is often summarised in modern philosophy as conceivability implies possibility. Despite being highly controversial, some philosophers find it rather appealing. And for several reasons.

1.

It seems to align with our intuitive way of thinking about possibility — we often use our ability to imagine scenarios as a guide to what could be. This is especially true when it comes to thought experiments. In fact, the premise 'if it is conceivable then it is metaphysically possible' is often key in the argument of many thought experiments.

2.

The idea that conceivability implies possibility provides a method for understanding what might be possible through pure reasoning — without the need for empirical evidence. This is particularly valuable when empirical investigation is impossible or impractical. It suggests we can gain insights about possibility solely through thought, which is a powerful tool in philosophy.

For example, Descartes used this type of reasoning in his philosophical investigations. Here's a simplified version of one of his arguments:

Premise 1: I can clearly conceive of a scenario where I could exist without a body.

Premise 2: If we can clearly conceive of something, then it is possible.

Conclusion: Therefore, it is possible that I could exist without a body.

3.

Finally, the 'conceivability implies possibility' principle allows us to explore counterfactual scenarios and potential alternate realities. For instance, we can imagine how history might have unfolded differently: it seems possible that Hitler could have been accepted into art school, potentially altering the course of the 20th century. This kind of thinking isn't just an academic exercise; it can have practical value, too. When we think about what might have been, we think about the consequences of alternative realities and can use this to learn and make better decisions.

The idea that conceivability implies possibility is critical for figuring out what is metaphysically possible. It allows us to think about what might be possible without needing empirical evidence. So, it would be great if conceivability did, in fact, imply possibility. But does it?

Q3: Are There Limits to Our Conceptions?

There are several objections to Hume’s maxim. Many of these objections question what it means to conceive of something, or they highlight that some things could only be known to be possible with empirical evidence. We'll cover some of these objections when we explore specific thought experiments. But for now, I want to focus on two arguments against the conceivability implies possibility principle; both address limitations in our ability to conceive.

Limitations in Our Knowledge

The first objection to Hume's maxim comes from philosopher Mary Shepherd.

She starts by quoting Hume:

Is there anything unintelligible about supposing that all the trees will flourish in December and lose their leaves in June?

Normally (at least in the northern hemisphere), most trees flower in June (i.e. the warmer months) and lose their leaves in December (i.e., the cooler months). But Hume supposes that we can conceive of a world in which trees flower in the winter and drop their leaves in the summer. He claims this statement is intelligible.

But Shepherd strongly disagrees, claiming:

there cannot be a more unintelligible proposition than to assert of those trees, which have usually flourished in May and June, that they may cease to do so, and only thrive in December and January.

Shepherd argues that once we understand how a tree works — it flowers in the summer months when it is warm and drops its leaves in the winter months when it is cold — it becomes not just implausible but genuinely inconceivable that the tree would flower during the colder months and drop its leaves during the warmer months.

Sure, Shepherd acknowledges, we might be able to imagine a tree flowering during winter. But this imagined tree could not be the same as the real tree. The imagined tree would lack the essential properties that make the tree a tree that flowers in summer.

Shepherd reasons that the more we learn about the nature of things, the less we find genuinely conceivable. Put another way, as long as we are ignorant about things, many things seem possible.

Limitations in Our Imagination

The second objection to Hume's maxim comes from philosopher Peter van Inwagen.

He argues that we might think we are imagining a situation or conceiving of a thing, but we very often are not actually imagining what we think we are imagining.

For example, he has us imagine a world with transparent iron.

If we simply imagine a Nobel Prize acceptance speech in which the new Nobel laureate thanks those who supported him in his long and discouraging quest for transparent iron and displays to a cheering crowd something that looks (in our imaginations) like a chunk of glass, we shall indeed have imagined a world…

But would this be a world in which there is, in fact, transparent iron?

van Inwagen argues that it would not be.

He asks us to consider what it is we are actually imagining when we think about a world with transparent iron. Are we imagining something that looks like glass but we just call it iron? In this imagined world, the object on display could be transparent iron — that’s true. But it could also be a piece of glass and the crowd is being tricked into thinking the item on display is a piece of iron.

So, we are left wondering: What am I imagining in the situation? Am I imagining a world in which there is truly transparent iron? Or am I imagining a world in which people are unaware of the facts? In this imagined world, it might be true that there is transparent iron, but it might also be true that there isn’t, and people are simply being tricked into thinking there is transparent iron.

What would we need to imagine to truly imagine a world that had transparent iron? van Inwagen argues that to truly imagine transparent iron, we would need to imagine the structural details of the iron, and we would have to imagine that this structure was, in fact, iron, and we’d have to imagine how this structure allows light to pass through. In fact, he claims,

our imaginations would have to descend to “a level of structural detail comparable to that of the imaginings of condensed-matter physicists who are trying to explain superconductivity.”

He concludes:

To my mind, philosophers who are convinced that they can hold, say, the concept of transparent iron before their minds and determine whether transparent iron is possible by some sort of intellectual insight are fooling themselves. (They could be compared to an inhabitant of the ancient world who was convinced that he could just see that the moon was about thirty miles away.)

The Sum Up

The concepts of possibility and conceivability are big and complicated topics in philosophy. This article merely scratched the surface. So, we should consider it a springboard to start a conversation, not the conclusion of any debate.

Next, in this series, we’ll start exploring specific thought experiments. As we encounter each scenario, we'll need to carefully consider two questions: What exactly are we being asked to imagine? And which type of possibility — logical, physical, or metaphysical — are we being asked to consider?

Thank you.

I want to take a small moment to thank the lovely folks who have reached out to say hello and joined the conversation here on Substack.

If you'd like to do that, too, you can leave a comment, email me, or send me a direct message. I’d love to hear from you. If reaching out is not your thing, I completely understand. Of course, liking the article and subscribing to the newsletter also help the newsletter grow.

If you would like to support my work in more tangible ways, you do that in two ways:

You can become a paid subscriber

or you can support my coffee addiction through the “buy me a coffee” platform.

I want to personally thank those of you who have decided to financially support my work. Your support means the world to me. It's supporters like you who make my work possible. So thank you.

Excellent post Suzi! I had no idea the tradition of conceivability implying possibility went that far back. It explains why so many philosophers seem comfortable with it.

I've always been skeptical of this idea, for exactly the reasons laid out by the philosophers you cite. We may *think* we can imagine something with sufficient rigor that it's meaningful, but human minds are more limited than that. I sometimes wished philosophers had to take some programming courses, primarily so they could internalize how bad humans are at logic.

I think thought experiments are useful devices, but mainly for clarifying people's intuitions. The best ones challenge those intuitions, find where they start to break down or become contradictory. But most are simply telling a story that validates the author's intuitions. The ones people find compelling are the ones that validate their own intuitions. It seems like their main value is in the conversation they generate.

But I've never been wild about the word "experiment" being in the name. That implies they tell us something about reality. Daniel Dennett called them "intuition pumps", which I think is an improvement, although to me "intuition clarifiers" might be more accurate.

Anyway, looking forward to the rest of the series!

Great article.

I think it’s useful to distinguish between imagination and conceivability. Conceivability means without logical contradiction, it’s a disciplined imagination. It’s a way of clarifying our concepts.

And the other thing is that while conceivability may not reliably tell us what is true, it is reliable in ruling out the false. So, when you say it doesn’t tell us “anything” about whether something is possible in the real world, it can tell us that square circles and married bachelors don’t exist. It rules out the impossible as false, rather than establishes the possible is actual.

Thinking about that in the context of the p-zombie thought experiment, it’s not suggesting zombies actually exist, it’s arguing “against” the idea there is an identity between mind and brain. If there was such an identity, there would be a contradiction in the concept of p-zombies.